While it was relatively easy to find fault with Ptolemaic astronomy, both on the observational as well as the theoretical level, and to criticize it as soon as it was being translated into Arabic, as we have seen in the section on ‘Critiques of Ptolemaic astronomy’, still finding alternatives to it was not an easy matter. That pursuit was further complicated by the fact that the motivation for finding alternatives to that astronomy was not in itself overwhelming. The reason being that Ptolemaic astronomy could, on the whole, still predict the positions of planets within a level of accuracy that would satisfy most practitioners of astrology who were its main users and only needed some basic numerical values to cast their horoscopes.

For the more serious astronomers, the question was much more intricate, for it involved the very foundation of Greek astronomical theory on many levels. First, there was the level of this theory’s consistency with the prevailing cosmology, namely that of Aristotle, a cosmology that was explicitly accepted by Ptolemy himself. Then there was the level of the suitability of Ptolemaic astronomy to describe the behavior of the real aspects of that cosmology, all represented as spheres in motion. That is, given the Aristotelian universe, formed of spheres moving in place at uniform speeds around axes that pass through their centers, and exhibiting a variety of observable phenomena, could Ptolemaic astronomy with its representation of those spheres by their mathematical properties also exhibit a consistent picture of the real world of spheres that was imagined by Aristotle and still explain that variety of observable phenomena?

And finally, there was the level of accounting for the observed phenomena by consistently using the same mathematical language that was used to describe the motion of the spheres, and to do so in such a way that did not violate the very mathematical definitions of those spheres. That is, if one were to use a set of mathematical definitions to describe a sphere in motion, thus, for example, describing any point on its surface as producing a circle whose center would have to fall along the axis of rotation which itself will have to pass through the center of the sphere if the sphere were to move in place, then could one use the same mathematical definition of that sphere and its properties while in motion, now represented by mathematical models as the ones we shall describe in the sequel, to describe how a planet is moved by such a sphere in order to appear the way it appears to an observer on the Earth?

The task of the alternative astronomy had to be set within the parameters of those questions. For that reason, it is easy to see why that purpose could not be achieved by simply pointing out the inner contradictions of Ptolemaic astronomy as was done extensively by various people, from the ninth century onward. Rather, in the words of a thirteenth-century astronomer al-ʿUrḍī, what was required was to create a new astronomy that did not suffer from the same handicaps that plagued Ptolemaic astronomy and not be satisfied with criticism only as was done by earlier astronomers.

This does not mean that earlier critics did not see the same need to formulate a new astronomy. In fact, one of the most vocal critics of Ptolemaic astronomy, Ibn al-Haytham himself, had occasion, in the context of his critique, to repeat several times, during his argumentation against Ptolemaic astronomy, that one must seek a new astronomy that did not suffer from the same problems. His argument was simple. It said: since the world was real, then there must be an astronomy that could describe the behavior of this real world in a manner that did not transform the real existing world into an imaginary one. Looked at differently, those earlier critiques could then be seen as establishing the new contours of the new astronomy, although they did not themselves produce that astronomy.

Before we proceed to demonstrate the manner in which the various astronomers, who took up the challenge of creating new alternatives to Ptolemaic astronomy, could conceive of their own new alternative astronomical theories, we should at this point review very briefly the basic mathematical structures of Ptolemaic astronomy itself, faults and all, in order to appreciate the modifications that were proposed for them.

In that regard, Ptolemaic mathematical structures, or planetary models, could be divided into two categories: those that represented the various motions of the planets in longitude and those that represented their motion in latitude.

For the first, there were four basic models that were proposed by Ptolemy in order to represent the motions of each of the following: the Sun, the Moon, the upper planets (i.e. Saturn, Jupiter, Mars), and Venus, which shared the same features as the other three in its longitudinal motion, and the planet Mercury.

For the latter, Ptolemy only made a distinction between the planets that moved in latitude as a result of the motion of their inclined planes, and/or as a result of the motion of their epicycles. Thus he made a distinction between the motion of the upper planets (here taken to be only Saturn, Jupiter and Mars) that exhibited a variation in their latitude motion as a result of the motion of their epicycles while their inclined planes remained fixed with respect to the ecliptic, and the inferior planets (Mercury and Venus) that exhibited a similar variation but as a result of the motion of both their epicycles as well as the inclined planes that carried those epicycles.

The Moon’s orbit, which is centered around the Earth, and the epicycle are both fixed with respect to the ecliptic and thus do not have any variation in latitude to be accounted for by a new latitude model like the others. In effect, the main component of the lunar variation in latitude is similar to that of the solar declination and can be computed in a similar fashion before adding the other variables.

The description of the solar motion is detailed by Ptolemy in Book III of the Almagest. And since that book marks the beginning of his treatment of the planetary motions, he used that occasion to set down the general ground rules of his astronomy, and enunciated the fundamental cosmological assumptions governing it.

Because of the relevance of those assumptions to the rest of his astronomy, and the problems resulting therefrom, it is worth reviewing them at this point as well as review the manner in which Ptolemy proposed to embody them in his mathematical structures.

Ptolemy’s discussion of the solar motion starts with an analysis of the length of the solar year, hence attempting to establish a periodic mean motion of the Sun which is a basic parameter for the rest of his astronomy and is at the same time a fundamental component of developing a model for the solar motion itself. In this respect Ptolemy approached the problem on two levels: First he supplied the reader with ready-made tables that could be used for the computation of the mean position of the Sun at any time of the year based on the predetermined periodic motion. And second, he supplied numerical tables that could be used for the computation of the true variations in the solar motion.

In both cases, however, he wished to make sure that the motion represented numerically in the tables was also understood to comply with the assumed cosmological assumptions already inherited from Aristotle. On this point in specific, he states explicitly:

that the mathematician’s task and goal ought to be to show all the heavenly phenomena being reproduced by uniform circular motions [obviously resulting from the motions of spheres in place], and that the tabular form most appropriate and suited to this task is one which separates the individual uniform motions from the non-uniform [anomalistic] motion which [only] seems to take place, and is [in fact] due to the circular models; the apparent places of the bodies are then displayed by the combination of these two motions into one (Almagest, III, 3).

It is clear from this statement that Ptolemy conceived the celestial motions as resulting from two types of motions: the periodic mean motions that can be pre-calculated for any time, and the irregular anomalistic motions of individual planets that can be added to or subtracted from the mean motions in question in order to determine the real positions of the planets. Both types of motion had to be accounted for as motions of real spheres moving uniformly in place, thus producing real uniform circular motion, despite the fact that they do not appear to be doing so for an observer on the Earth. In addition, what appears to the observer to be irregular motions of individual planets had to be explained still in terms of such spheres whose uniform motions can now be calculated and tabulated in order to facilitate their use.

Next, Ptolemy went on to consider the nature of uniform motion itself in Book III, Chapter 3. And here he was faced with cosmological questions that he had to account for. He agreed with Aristotle that all uniform motions had to be carried out by spheres moving in place. In his own words:

But first we must make the general point that the rearward displacements of the planets with respect to the heavens are, in every case, just like the motion of the universe in advance, by nature uniform and circular (ibid.).

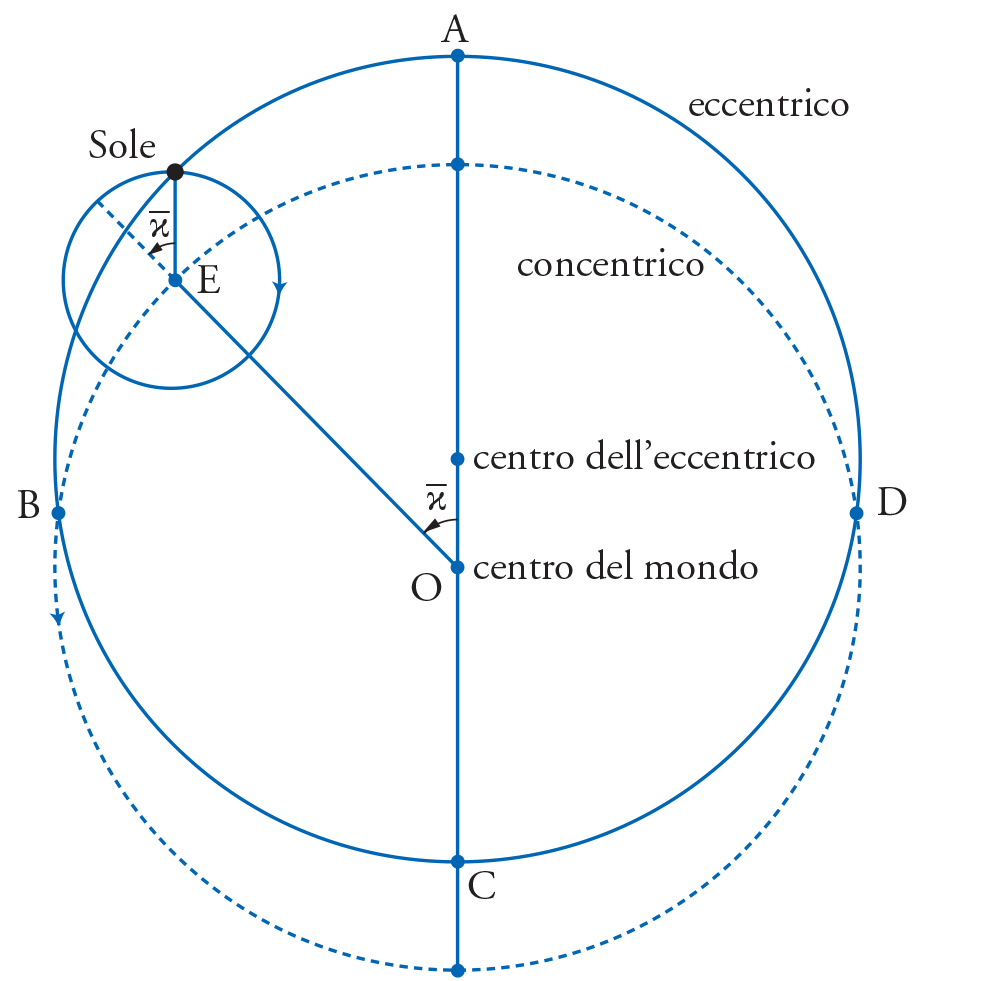

But he could not agree completely with the second Aristotelian requirement, namely, that all moving spheres had to be concentric with the Earth, which was the center of heaviness and had to be placed at the center of the world. For now, he had the observations to account for. Had the Sun been moved uniformly by a sphere concentric with the Earth, then we would not have any variation of seasons, and the Sun would not appear to be moving faster during fall and winter and slower during spring and summer. And the observations confirm this variation.

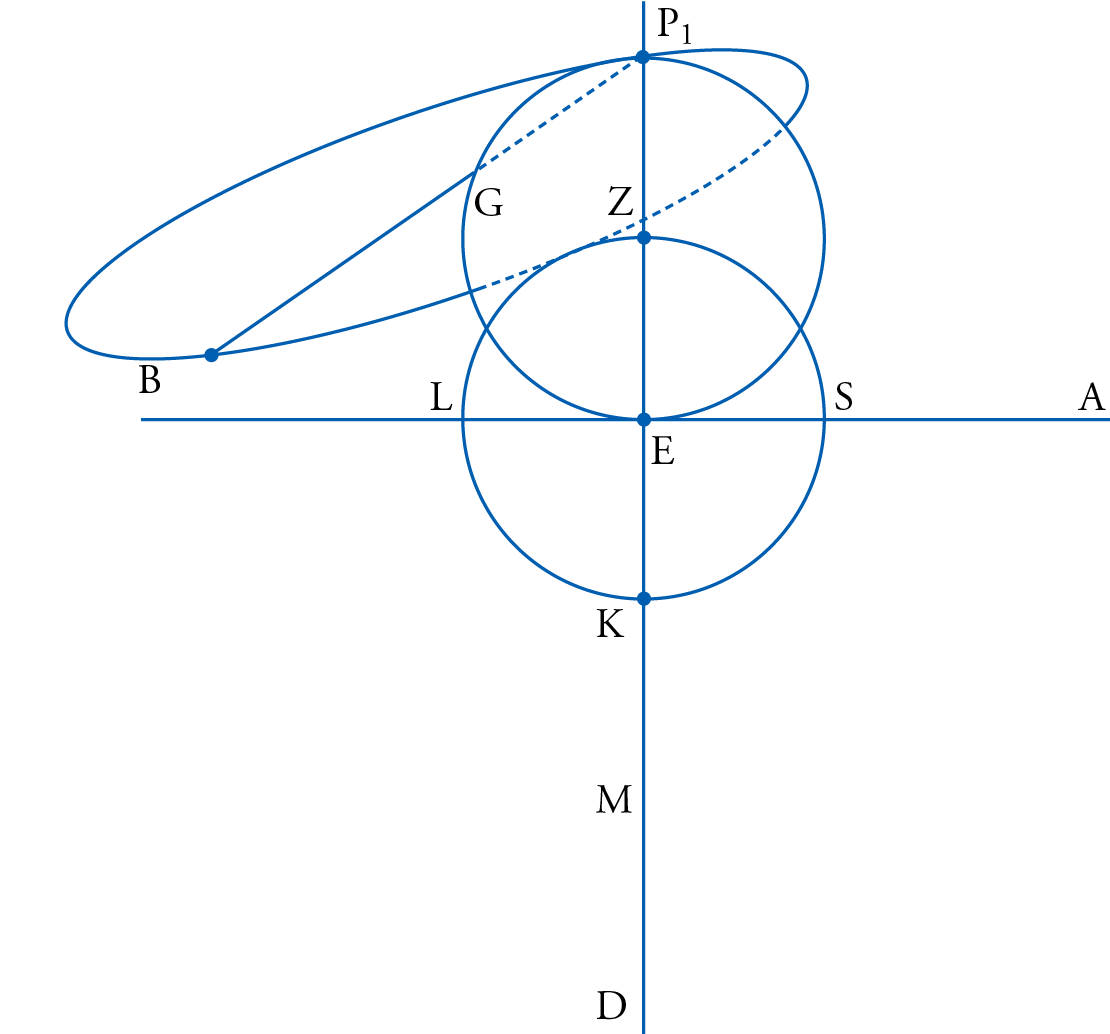

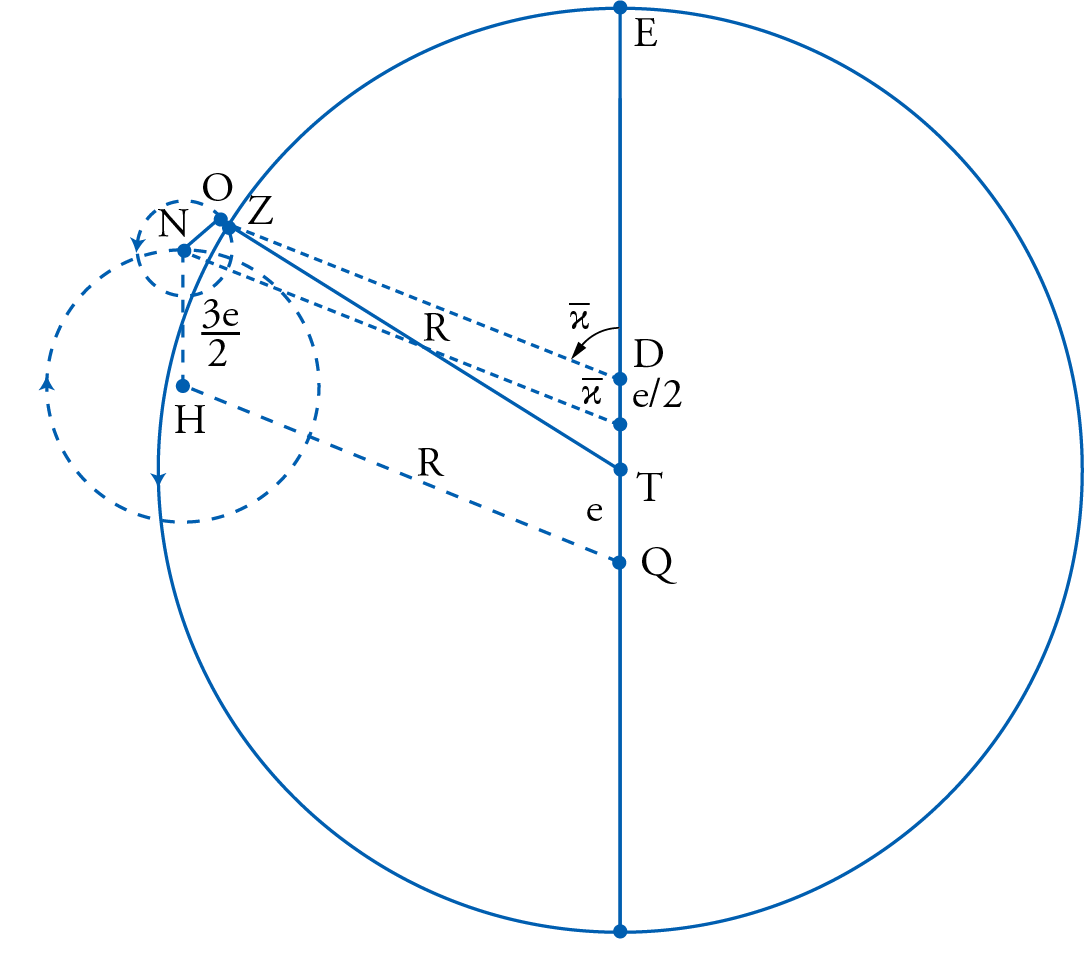

One could explain this variation away if one were to assume that the Sun was moved by a sphere that was slightly eccentric to the Earth, and represented in fig. 1 by the circle ABCD. But that would mean that the Aristotelian requirement of concentricity had to be abandoned. Otherwise, and in order to preserve the Aristotelian concentricity, one could imagine the Sun being moved uniformly by a small sphere, called an epicycle, here represented by a circle with center E, which was itself carried by another sphere, called the carrier or the deferent, concentric with the Earth.

The second alternative would violate the Aristotelian cosmology in another sense. For now, it would introduce the sphere of the epicycle, which was supposedly made of the same weightless element ether of which the rest of the celestial spheres and planets were made, whose center of motion E was not a center of heaviness as would have been required by any moving sphere.

So in either model the observer could be assumed to be placed on the Earth O, and the Sun would either move with the eccentric model (called “hypothesis” by Ptolemy) along circle ABCD (seeming to move slower around the apogee A and faster around C due to its distance or proximity from the Earth) or be moved by the epicyclic model along the epicycle with center E, in the direction designated by the arrow, and have the center of the epicycle itself now move around the Earth along the dotted circle in the designated direction.

Although both models of motion account quite well for the observable motion of the Sun, and were both mathematically equivalent as was already demonstrated by Apollonius (c. 200 BC) and here repeated by Ptolemy, they both violated the Aristotelian cosmological principles, each in its own way. Faced with these two options, and thus two violations of the same principles that he had just accepted emphatically, Ptolemy opted for the lesser of the two evils, without saying so explicitly, and settled for the eccentric model on account of its “simplicity” (Almagest, III, 4).

No further discussion of the cosmological principles was raised, except to say that in the case of the Sun one had those two alternative hypotheses to account for its motion, while in the case of the other planets, that would be discussed later, the observations required that both hypotheses be used together in order to account for the complicated motions of those planets. In his own words: “for bodies which exhibit a double anomaly both of the above hypotheses may be combined, as we shall prove in our discussion of such bodies” (ibid., III, 3). The rest of the book was devoted to the proof of the equivalence of the two hypotheses, the numerical tables of the solar anomaly, and a discussion of the variation in the solar days.

Although the order of presentation in the Almagest proceeded from the solar model to that of the Moon, for reasons that had to do with the pedagogical arrangement of the Almagest, for mathematical models that are related to cosmological principles, which generated much discussion in Islamic astronomical works, the mathematical model for the upper planets, namely, Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, and Venus, is simpler to present here for it embodies an application of both of the hypotheses just discussed. For the sake of that simplicity we shall now turn to the model of the upper planets, and leave the more complicated motions of the Moon and Mercury till the end.

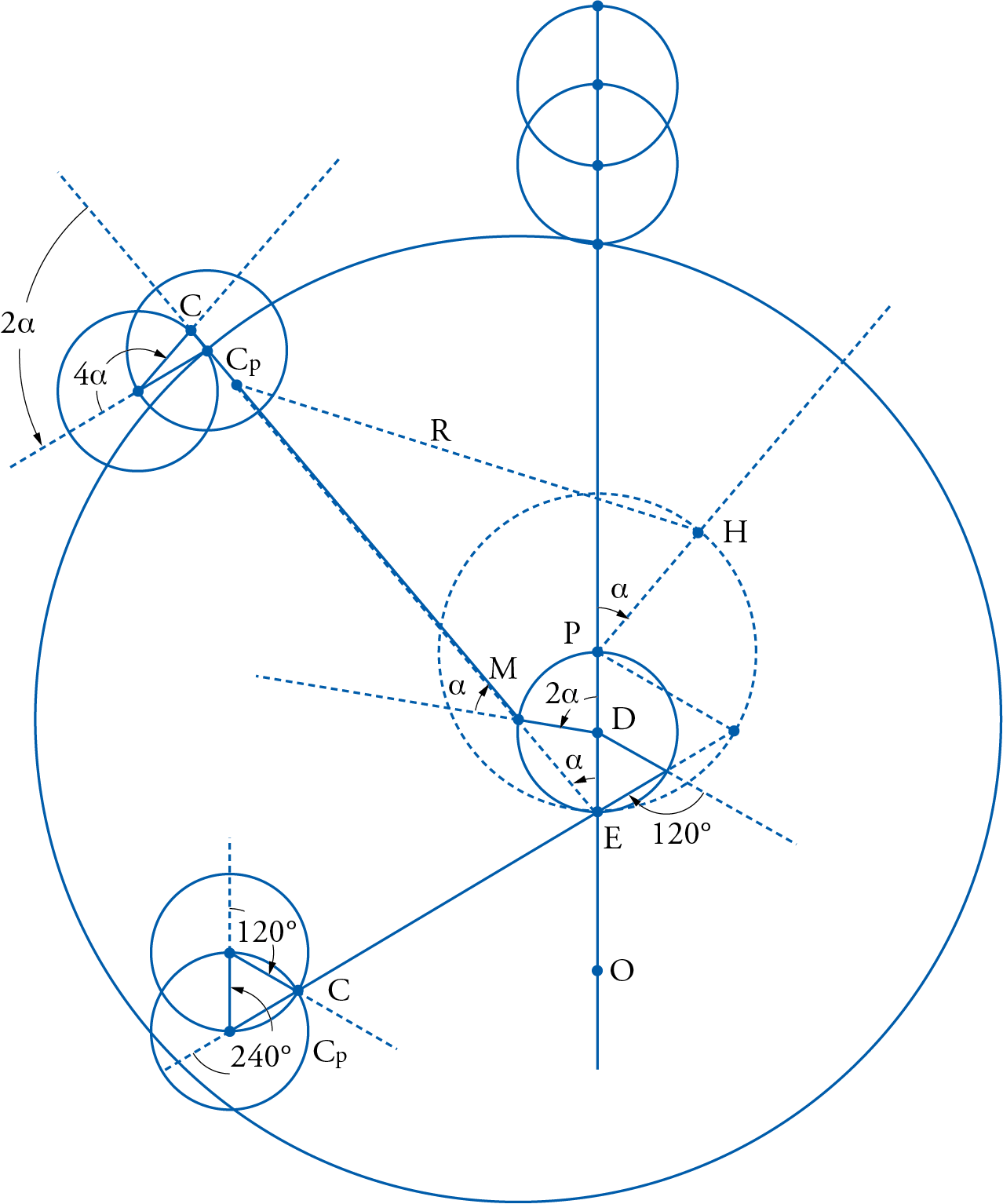

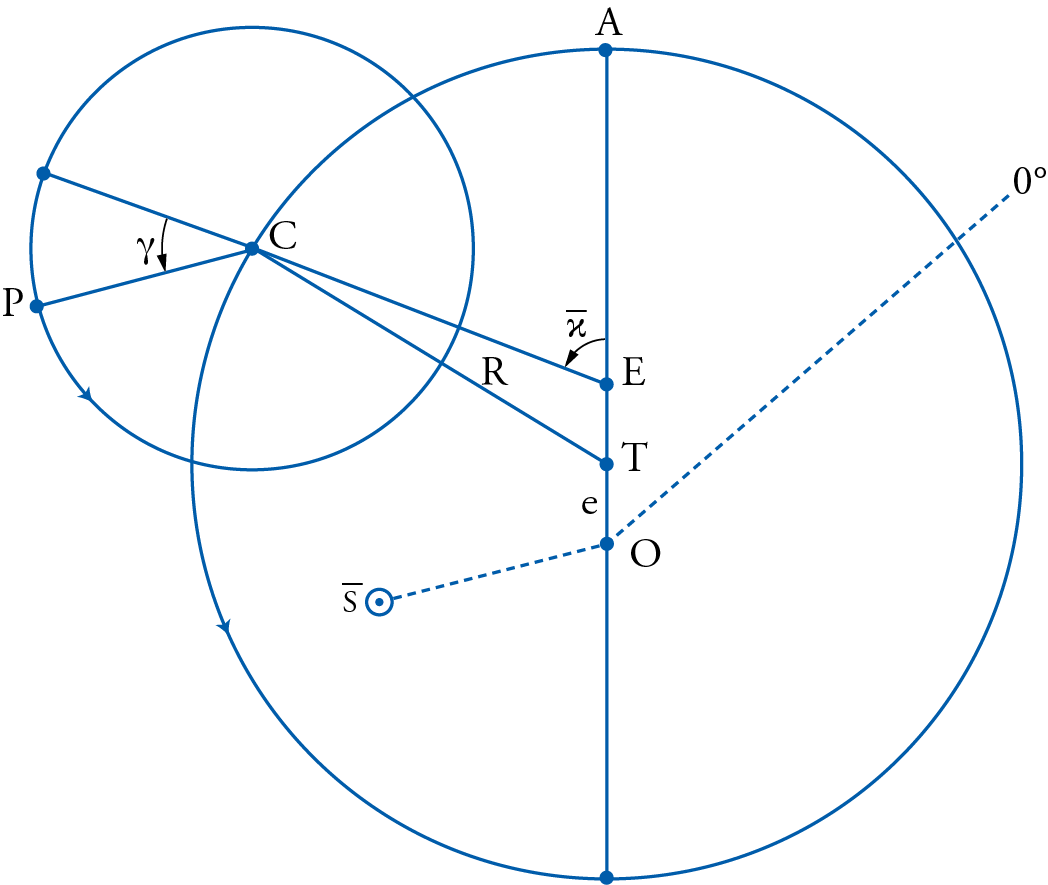

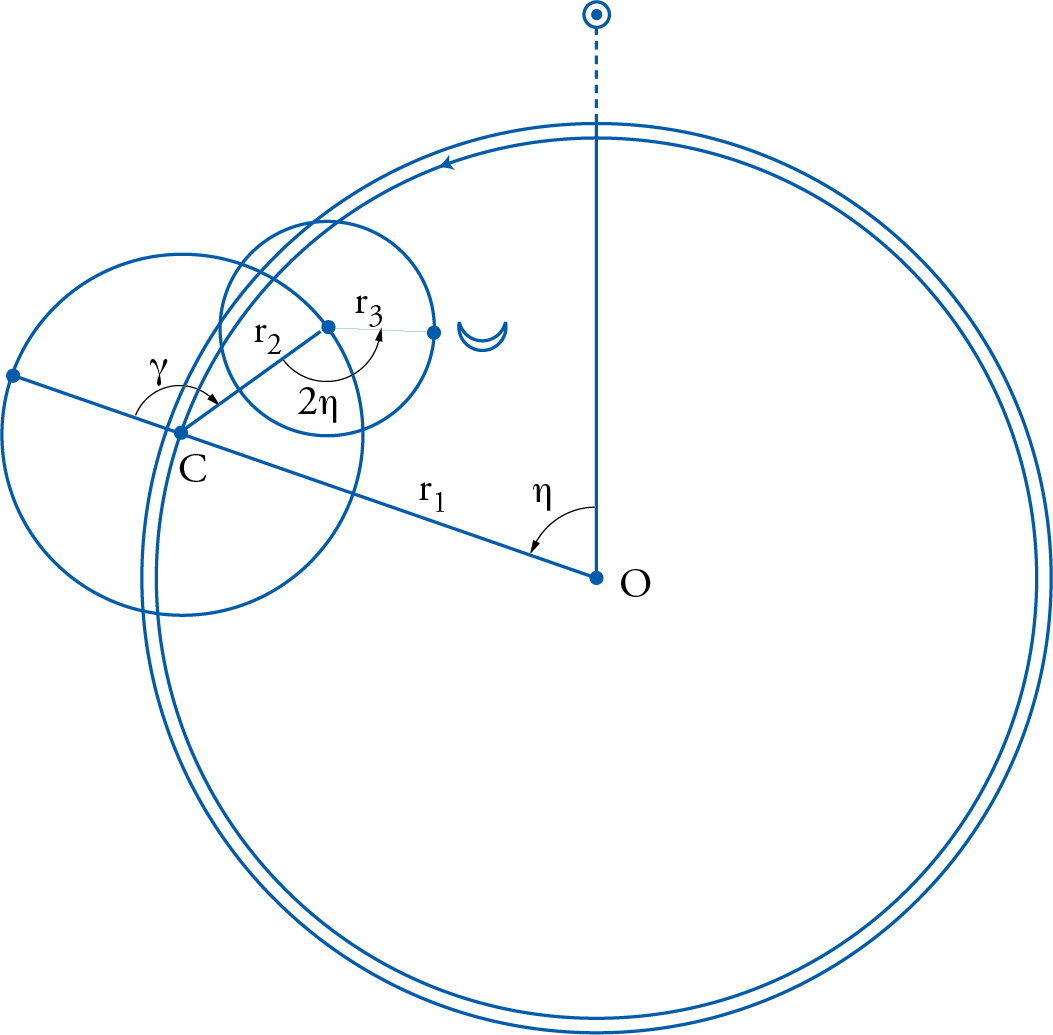

Ptolemy described the motion of the upper planets (Saturn, Jupiter, Mars) and Venus in Book IX of the Almagest. In the summarized form it took in Almagest IX, 6, and with reference to fig. 2, the motion of those planets can be described as follows. For an observer on the Earth at the center of the ecliptic or the world, O, the planet P looks like it is moved by its own epicycle with center C, at a uniform anomalistic speed \(\gamma\).

The direction of the motion is marked by the arrow on the epicycle, and is usually designated by Ptolemy as being in the direction of the rear of the signs, or as in later Islamic sources as being in the direction of the ascending order of the signs. The point on the epicycle’s circumference from which this anomaly is measured is defined by the extension of the line that connects the center of the epicycle to a fictitious center E, later called the equant, which is neither the center of the world O, nor the center T of the deferent sphere that carries the epicycle.

Ptolemy’s contention is that the epicycle sphere with center C is carried in the same direction of the order of the signs, marked by the arrow in the diagram, by a deferent sphere with center T, which is itself eccentric with respect to the observer at point O. This is the application, mentioned earlier, that combines both the eccentric as well as the epicyclic hypotheses that were mentioned before as alternatives for the motion of the Sun only, and were here used to describe the motions of the upper planets. Similar double usage was also made in the cases of the Moon and Mercury as we shall see in the sequel.

Although this construction for the upper planets accounted rather well for their motion in longitude, it had its own fundamental drawbacks. On the positive side it allowed the planets to progress in their mean motion from west to east, i.e. contrary to the direction of the primary daily motion of the heavens, and in the direction of the ascending order of the zodiacal signs Aries, Taurus, Gemini, etc. The planet’s own motion was measured however by the mean motion of the epicyclic center C along the circumference of the deferent with center T, which was itself eccentric with respect to the observer, thus allowing for a slow and fast motion as the center of the epicycle approached, in its mean motion, the apogee A and receded away from it. Furthermore, with their motion around their own epicycles they would exhibit their forward and retrograde motions as well as their stations in between.

But on the negative side, the deferent with center T, according to this construction, would be forced to move uniformly not about an axis that passed through its own center T, but rather about an axis that passed through the equant E. This was the reason why the line joining E to the center of the epicycle C, when extended, determined the mean epicyclic apogee from which the planetary anomaly was measured. Furthermore, the very same line, EC, was used to measure the mean motion of the epicyclic center C, i.e. measure the mean uniform motion of the planet.

From the point of view of cosmology, and assuming the spheres of the deferent as well as that of the epicycle to be real spheres obeying physical laws consistent with the properties of a sphere, as was implicitly and explicitly accepted by Ptolemy, this mathematical construction betrayed what was conceived to be a fundamental contradiction. That contradiction involved the absurdity of having a real physical sphere, in this case the deferent with center T, move uniformly about an axis that did not pass through its center, rather through a fictitious point E, simply designated as the ‘equalizer of motion’ and later abbreviated as the ‘equant’. In terms of uniform motion, it is quite obvious that, in this construction, point C did not describe equal arcs in equal times around the center of its carrier T, rather it did so around the equant center E, which had no physical reality per se. This was in essence the basic flaw that permeated the whole of Ptolemaic astronomy, for, as we shall see, similar manifestations of it appeared as well in the constructions describing the motions of the Moon and Mercury.

The lunar motion is much more complicated than the motions previously described. In Book IV of the Almagest, Ptolemy made a feeble attempt to accommodate the lunar motion with a model combining the main features of the solar model and adding to it an epicycle, i.e. in a construction similar to the one just described for the upper planets. But, with the variations in the positions of eclipses, the apparent motion of the Moon on its epicycle, and the apparent variation in the size of the epicycle of the Moon, he quickly realized that there were too many observational variables to be accounted for with such a relatively simple model. In Book V of the Almagest he moved on to construct a very intricate model to account for all those variations just mentioned, but at a great price as we shall soon see.

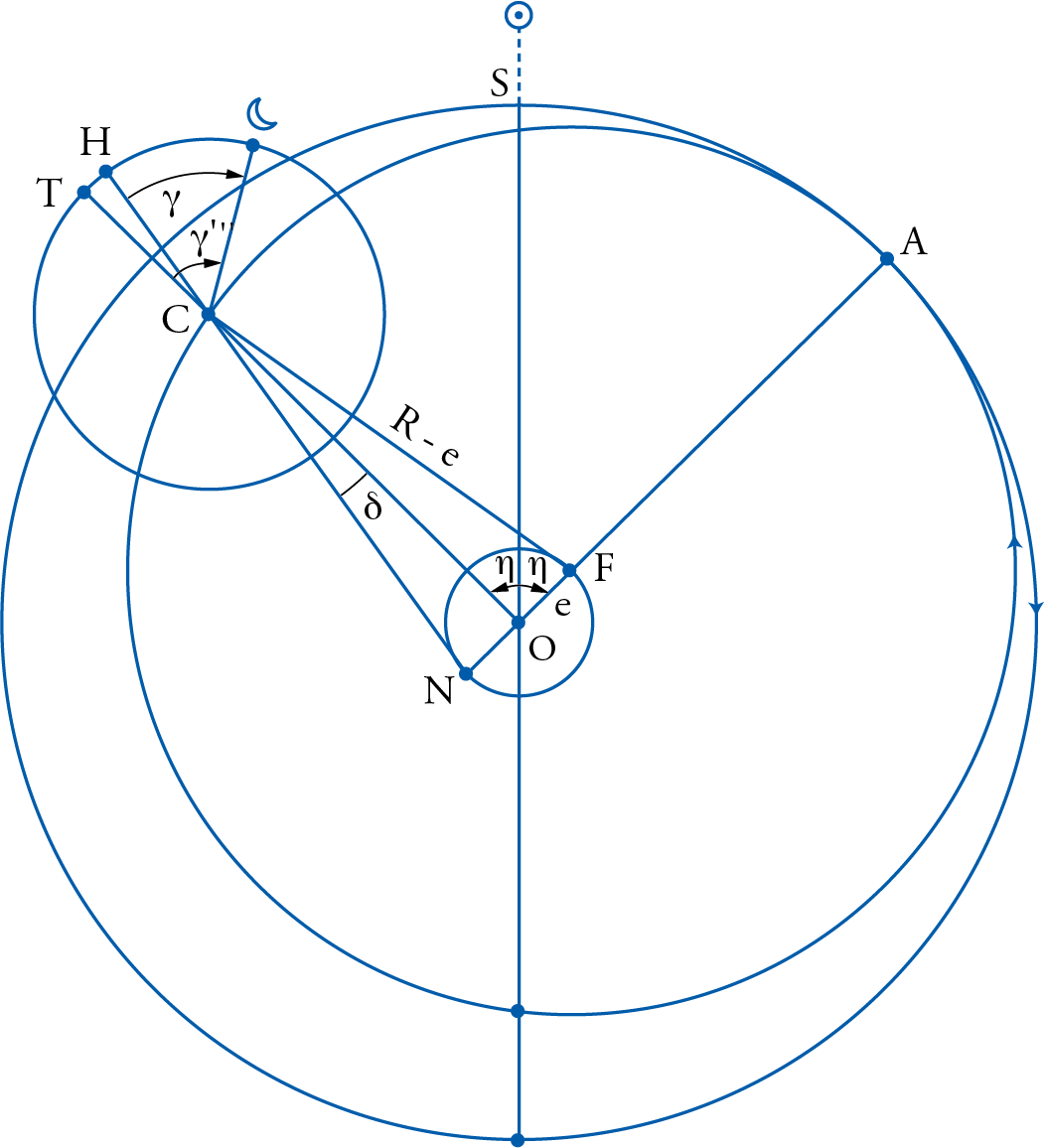

For an observer located at point O, the center of the world, and given the position of the mean Sun at point S (fig. 3), the Moon appears to move in the following manner. In order to account for the variations in the ecliptic coordinates of eclipses, the lunar nodes – namely, the two points at which the Moon’s orbit intersects the ecliptic – must be carried by a sphere that encompasses the entire system, referred to as the ‘sphere of nodes’ (not shown in the figure). This sphere moves uniformly around the center of the world, thereby transporting the apogee of the deferent, A. In turn, the deferent moves in the opposite direction around its own center F, in such a manner that the angles SOA and SOC are equal in magnitude but opposite in direction.

Another sphere – the outermost depicted in the figure – with a radius R and a fixed inclination relative to the ecliptic, moves in the direction indicated by the arrow, which is opposite to the order of the zodiacal signs. This inclined sphere moved at a speed equal to about 12° per day and moved with it all that was inside it, including the deferent sphere whose center F was eccentric with respect to the center of the world at a distance e, and whose apogee A remained equidistant from the observer on the Earth.

The deferent sphere itself moved by its own motion in the opposite direction, that is, in the direction of the succession of the signs, at twice the speed, and carried with it the lunar epicycle with center C. But its mean motion was measured with respect to the center of the world O, rather than its own center F. As a result of these two motions, the mean Sun S was supposed to remain always halfway between the apogee A and the center of the epicycle C.

In turn, the lunar epicycle carried the body of the Moon in the direction opposite to that of the succession of the signs, as is marked on the diagram, but measured its own mean motion from the extension of the line HC, that was directed neither towards F, the center of its carrier, nor towards O the center of the world, but towards a point N, called the prosneusis point, that was diametrically opposite to F from point O.

This crank-like mechanism allowed for yet another variation that was supported by Ptolemaic observations, namely, the variation in the apparent size of the epicycle, as it moved from conjunction with the mean Sun S where it had an apparent radius of about 5;15 parts of the same parts that make \(R=60\) producing a maximum variation of about 5° for an observer at point O, to a point that was 90° from the mean Sun where the maximum variation for an observer at O could reach as much as 7;40°.

But at the same time, this model produced three important inconsistencies. First, it shared the same defect as the previous model of the upper planets in that it stipulated the uniform motion of a sphere, in this case the deferent with center F, to take place about an axis that did not pass through its own center F, but rather through O the center of the world. Second, it stipulated the measurement of the mean motion of the Moon from the extension of the line joining the prosneusis point to the center of the epicycle. Finally, the crank-like mechanism that was supposed to account for the angular variation due to the change in the apparent size of the epicycle, also resulted in bringing the Moon so close to the Earth at quadrature that its own apparent size would become almost twice as large as the size it would have at opposition or conjunction with the Sun; a fact that was blatantly contrary to observation. Ptolemy said nothing about these discrepancies. But most of the objections that were raised against his lunar model later centered on those very same discrepancies as we shall see in the sequel.

The proximity of Mercury to the Sun and its relatively fast motion have always made this planet difficult to observe. As a result, Ptolemy had to rely on faulty observations, which led him to believe that the apparent motion of Mercury resembled that of the Moon, in that, over the course of its annual revolution around the Earth, it exhibits two perigees. These occur because its epicycle approaches the Earth twice – each time forming an angle of 120° with the apogee – and not only once, as is the case with the Moon. To account for this, Ptolemy resorted to a mechanism very similar to the one he had used for the Moon; and it is for this reason that we have chosen to present Mercury’s model immediately after that of the Moon.

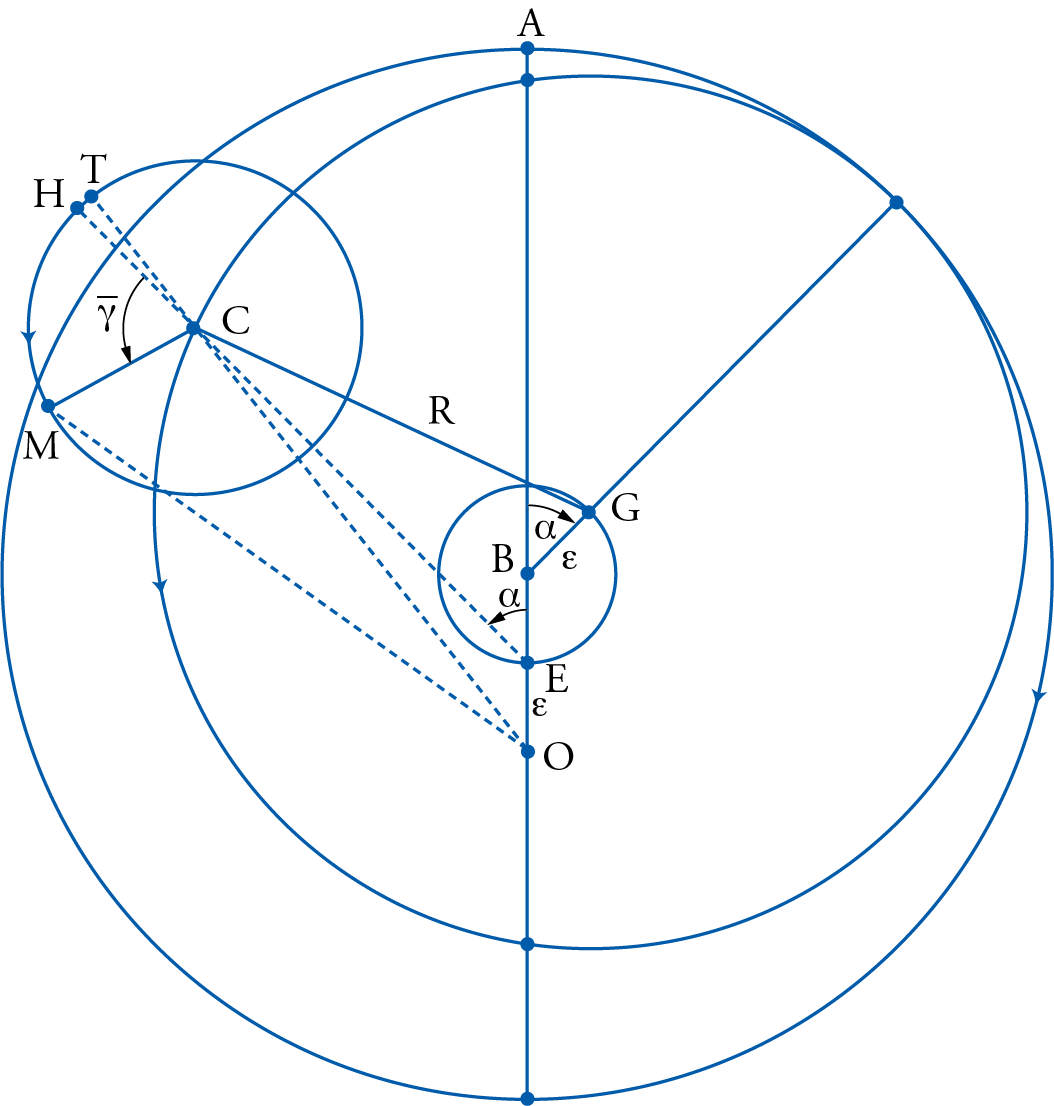

In the Almagest, however, the motion of Mercury is described in Book IX, immediately following that of the upper planets. It involves the mechanism depicted in fig. 4. An outer sphere, analogous to the inclined sphere of the Moon, is postulated to move in the direction opposite to that of the succession of the zodiacal signs, as indicated in the figure. The difference between this sphere and the lunar inclined sphere lies in the fact that, in the case of Mercury, this sphere – called the ‘director’ – is eccentric with respect to the center of the world, whereas in the case of the Moon, it is concentric.

The center of the director is located at point B, shifted toward the apogee A, which Ptolemy describes as “slow-moving.” Everything contained within the director is moved by its uniform motion, including the deferent whose center G is itself eccentric with respect to the center B of the director by an eccentricity equal to e. Consequently, the motion of the director forces the center of the deferent to describe a circle of radius e around its center B.

The deferent then moves by its own motion, independent from that of the director but equal in magnitude and in the opposite direction; with this motion, it carries the planet’s epicycle whose center is located at C. The planet itself is then moved by this epicycle in the direction of the zodiacal signs, as shown in the figure. However, the uniform mean motion of the planet on its own epicycle is measured – not unlike the case of the Moon – from a line connecting the center of the epicycle to a fictitious point E, called the ‘equant’: E is neither the center of the deferent that carries the epicycle, nor the center of the world where the observer is located, nor even the center of the director that produces the motion of the deferent just described.

Furthermore, similarly to the model for the upper planets, where the center of the deferent was postulated without proof to be halfway between the center of the world and the equant point, here too this new equant is also postulated without demonstration to lie midway between the observer and the center of the director.

Given what we already know about the fundamental cosmological assumptions accepted by Ptolemy, the problems with this model should be readily apparent. Here again, the uniform motion of the deferent is not measured with respect to its own center G, nor to the center B of the director that carries it. Instead, it is measured with respect to the equant E, which – as we have said – is located halfway between the observer at O and the director’s center B. Consequently, as in the two previous cases – the Moon and the upper planets – Ptolemy here too posits the existence of a sphere that moves uniformly in place without rotating about an axis passing through its center: a veritable physical absurdity. Most of the objections raised against this model were centered on this very inconsistency.

For the planetary motions in latitude, Ptolemy made a distinction between the upper planets (this time Saturn, Jupiter and Mars only as was said before) and the lower ones, Venus and Mercury. And like the longitudinal motions, most of the numerical results derived from his models agreed rather well with the observations, but contained similar cosmological inconsistencies, some of which had a bearing on the longitudinal motions themselves.

As far as the alternatives to Ptolemaic models that were developed later on in Islamic times were concerned, very few of them touching upon the latitudinal motions have been identified so far and studied and thus they will not preoccupy us here except in as much as they have a bearing on the longitudinal models themselves which are much better known.

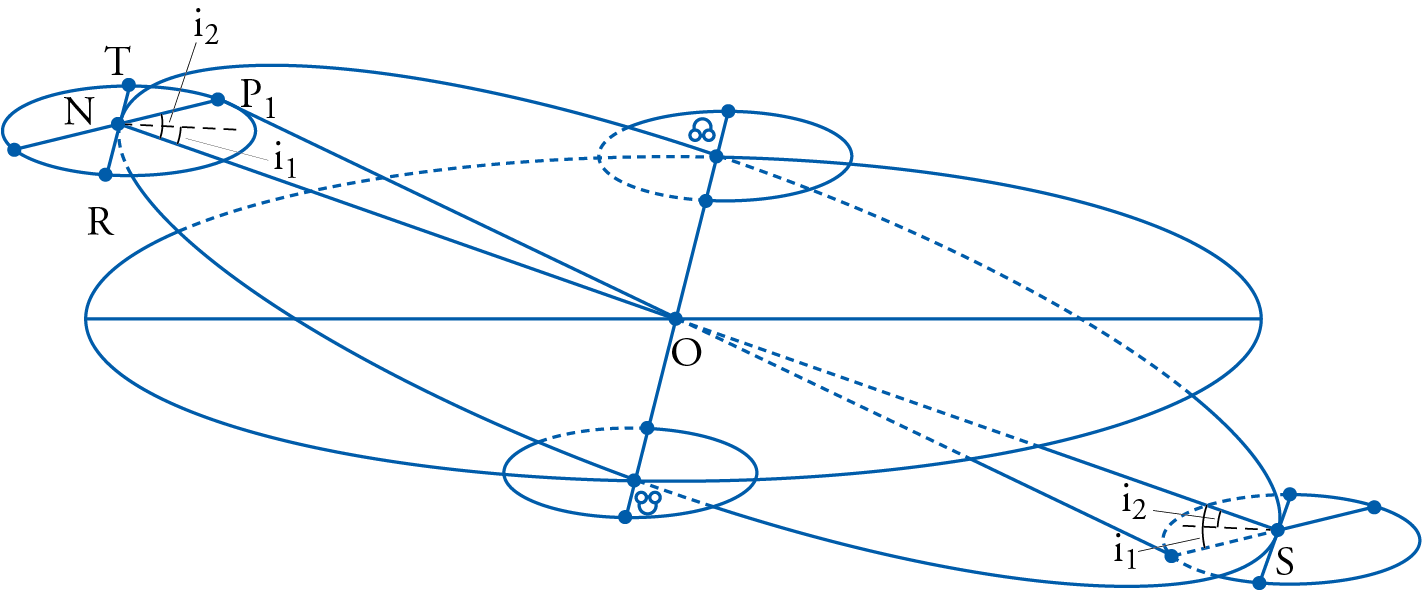

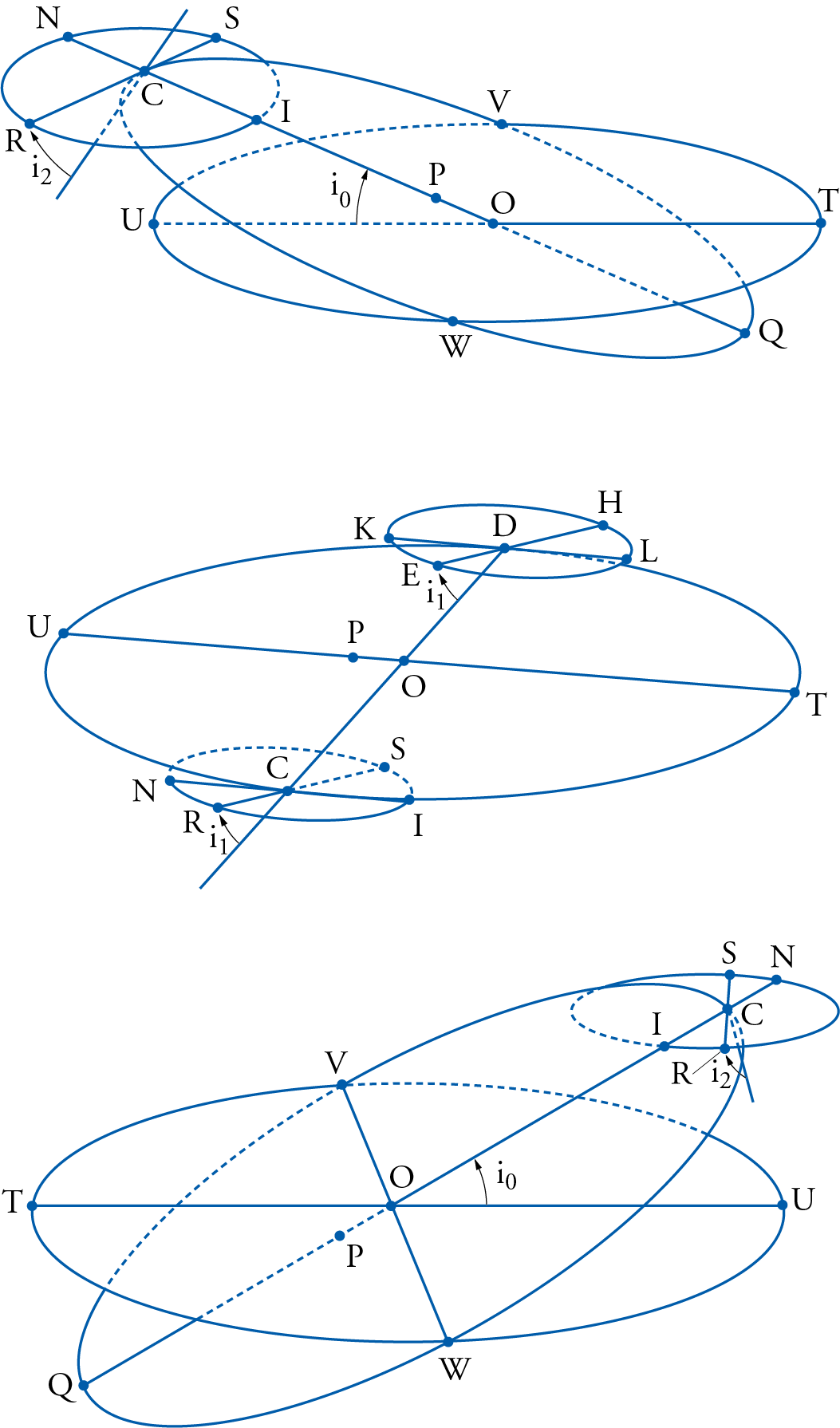

For the upper planets, Ptolemy proposed the configuration sketched in fig. 5. The observer was placed at point O, the center of the ecliptic, and the inclined plane of the deferent for the three upper planets was inclined with respect to the plane of the ecliptic at a fixed angle, here marked as \(i_1\).

The line of intersection between the plane of the deferent and that of the ecliptic marked the position of the two nodes, the ascending node (called the ‘head’) where the center of the epicycle crossed the plane of the ecliptic in its northward motion and the descending node (called the ‘tail’) diametrically opposite to it with respect to the center of the world.

The line perpendicular to this line of nodes passing through the center of the world, here marked as NS, was the line that determined the North and South portions of the deferent.

Now, while at the northernmost end of the deferent, the plane of the epicycle would itself be inclined by an angle \(i_2\) (called ‘deviation’), with respect to the plane of its own deferent, and thus reach its maximum northerly deviation \(i_2\). When at the southernmost end the same phenomenon occurs in the opposite direction producing the greatest southerly deviation also designated as \(i_2\), but of a larger apparent value than the northerly deviation since that portion of the deferent was closer to the observer. While at the line of nodes, the plane of the epicycle goes back to lie flat in the plane of the ecliptic.

In effect then the plane of the epicycle seems to be undergoing a seesawing motion about the axis TNR which was always parallel to the plane of the ecliptic. In order to account for this seesawing motion, which was quite ‘unnatural’ for the cosmology already accepted by Ptolemy, he proposed to place two ‘small circles’ placed at the real perigee of the epicycle \(P_1\), with their plane perpendicular to the plane of the deferent. If the radius of those ‘small circles’ was taken to be equal to the maximum deviation, then the tip of the diameter that was attached to them would perform the seesawing motion in the same period it would take the epicycle to go once around the deferent. But the northerly portion of the deferent was not equal to the southerly one as was just said, and thus the motion of the tip of the diameter \(P_1\) around the ‘small circle’ would not be uniform, and thus would require its own equant as in the case of the longitudinal motion.

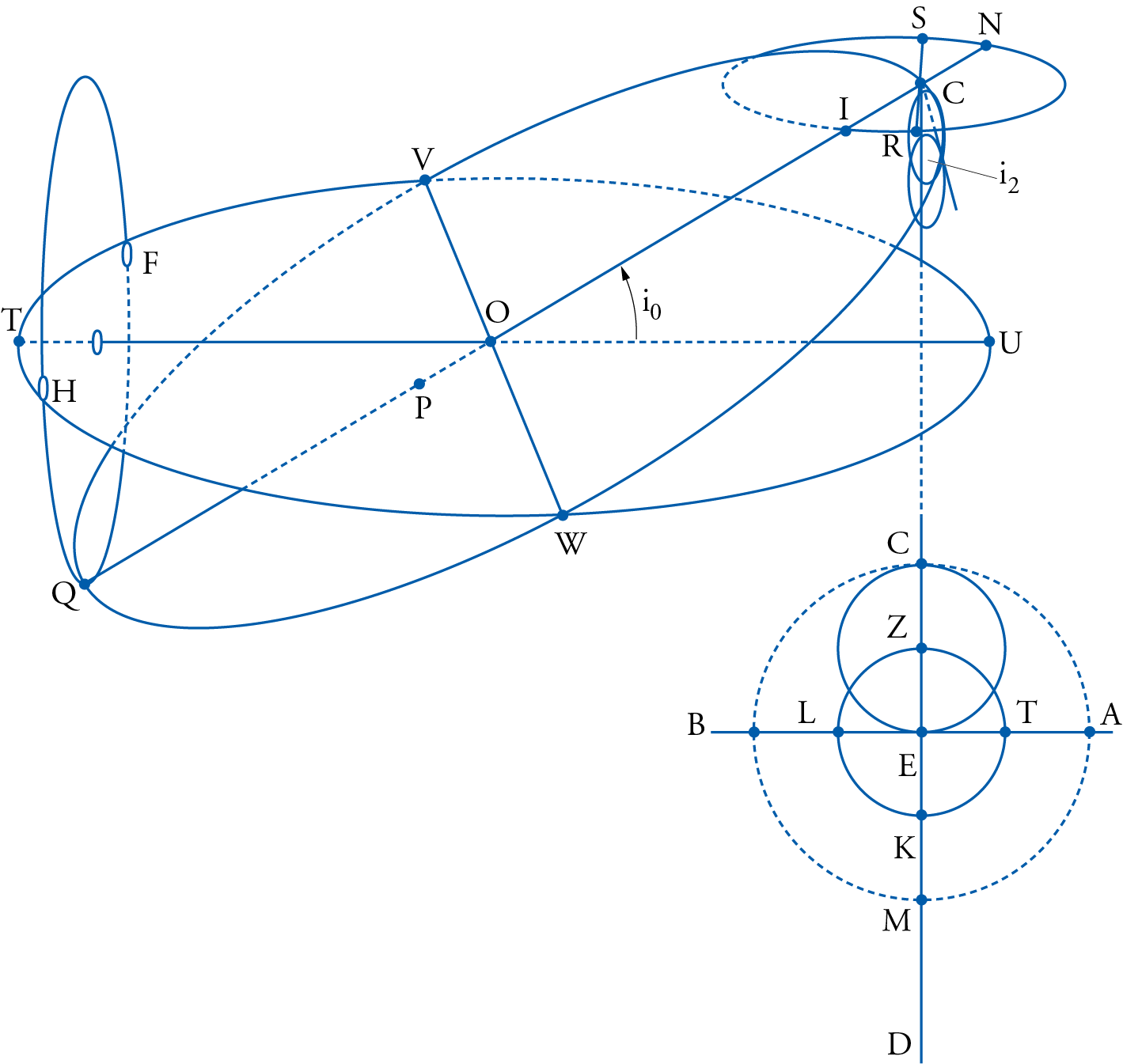

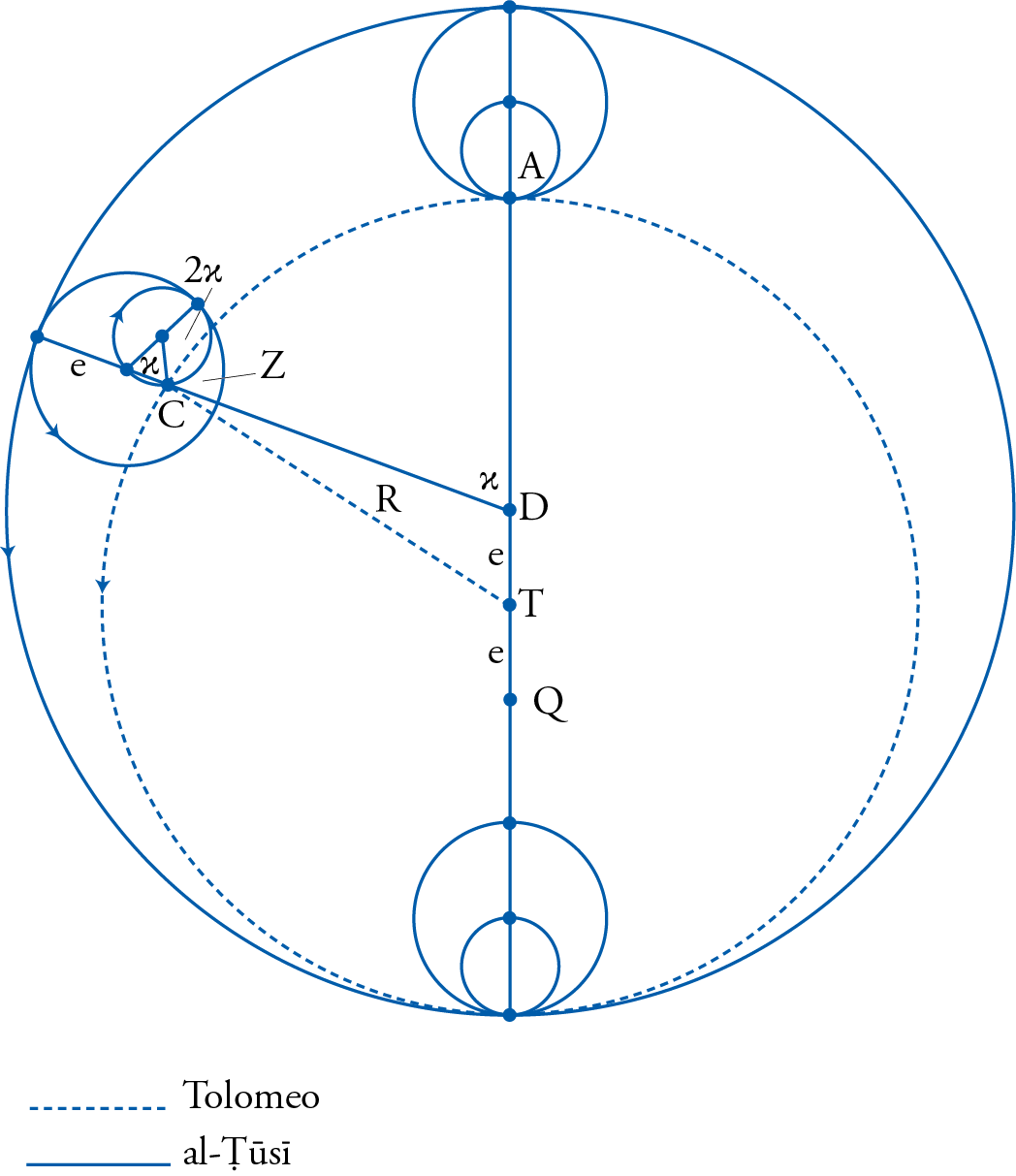

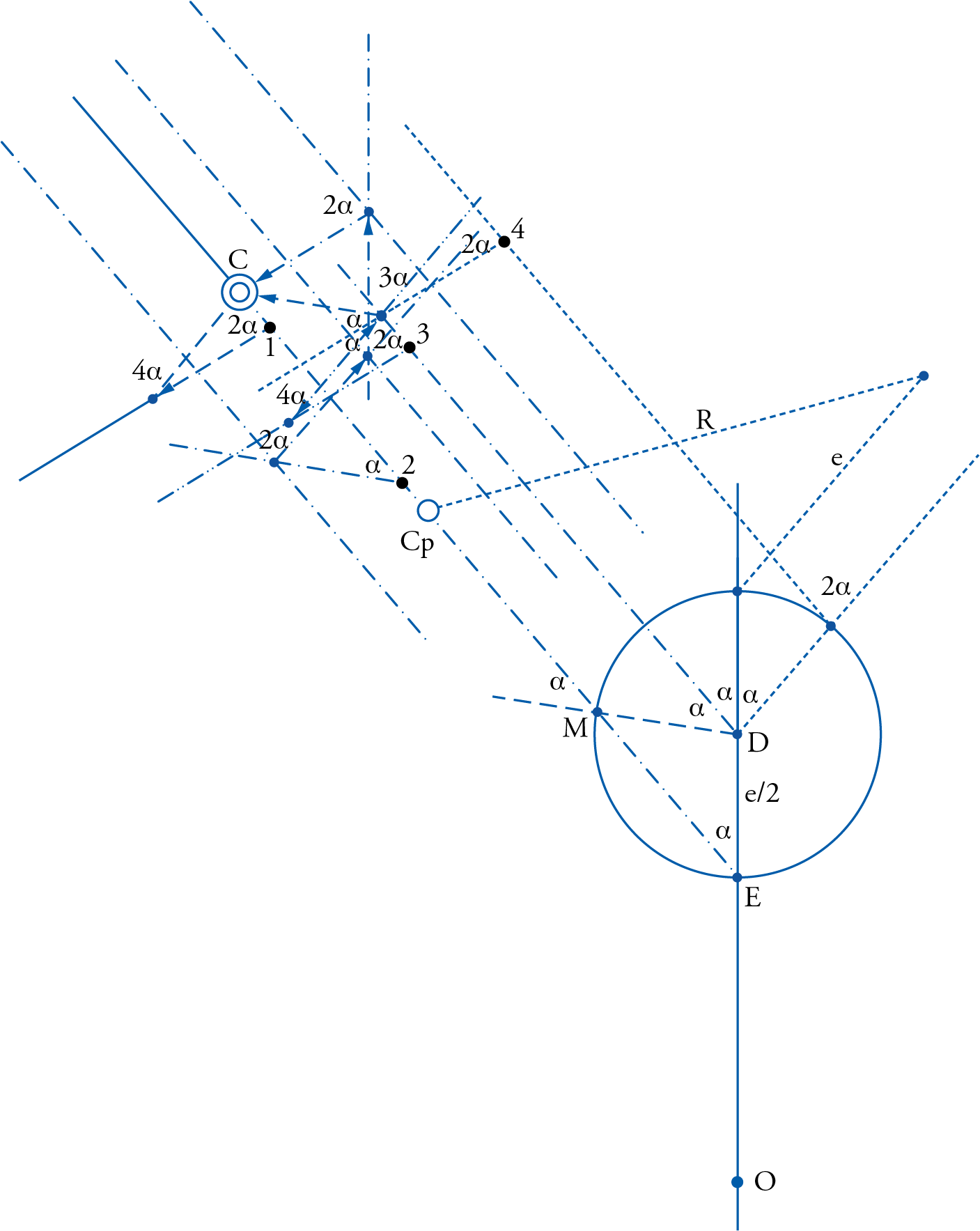

Besides, the motion of \(P_1\) along the circumference of a circle, although it would achieve a seesawing effect in latitude, it would also necessarily create a wobbling effect in longitude. This discrepancy was noted during Islamic times and was apparently objected to for the first time by Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (d. 1274), whose work we shall soon examine, in a commentary that he wrote in 1247 on the very same Ptolemaic Almagest in which this basic construction was proposed. It was at that point that al-Ṭūsī accused Ptolemy of saying things that were unacceptable in the craft of astronomy (ṣināʿa), and went on to propose a solution to the problem, whereby the tip of the diameter P₁ was made to move (fig. 7) on a circle \(P_1GE whose center Z would move on another equal circle ZLKS which would itself move in the opposite direction at twice the speed. The two circles, later generalized to become the Ṭūsī Couple (fig. 5), with their respective opposite and unequal, but uniform, motions had the virtue of allowing \(P_1\) to oscillate up and down about the same axis TNR, but also allowed it to remain along a straight line \(P_1E\) which formed the diameter of the primary circle instead of wobbling along the circumference as it did before.

The latitudinal motion of the lower planets is much more complicated than that of the upper planets. We will illustrate that motion for the planet Venus, since that of Mercury was conceived to be symmetrically opposite to it.

In figure 8a, 8b and 8c the observer was still supposed to be placed at point O. But the inclined plane of the deferent of Venus was not only inclined with respect to the plane of the ecliptic but its very inclination was not fixed as was the case with the upper planets. According to Ptolemy’s construction, when the epicycle was in the northernmost portion of the deferent (fig. 8a) the inclined plane reached its maximum inclination \(i_0\) in the northerly direction. At that point too, the plane of the epicycle itself was also inclined with respect to the plane of its own deferent by an easterly deviation of a maximum value \(i_2\), while its north-south axis, NI, remained in the plane of the deferent.

As the epicycle progressed along its own deferent to reach the line of nodes, the plane of the deferent itself collapsed to coincide with the plane of the ecliptic (fig. 8b). Only the epicyclic plane would have another deviation, here marked as \(i_1\). As the epicycle reached the southernmost direction (fig. 8c) the whole configuration flipped to produce a northerly inclination of the deferent plane at a maximum value of \(i_0\), and the plane of the epicycle would go back to deviate from the plane of its deferent by an angle of \(i_2\), while its north-south axis NI remained in the plane of the deferent.

In effect this configuration required two seesawing motions, one for the inclined deferent plane and the other for the plane of the epicycle itself. Here too the seesawing motions were taken care of by the introduction of the same ‘small circles’ mentioned above in the case of the upper planets. And as before one had to imagine that in addition to a ‘small circle’ that would allow the epicycle to seesaw, one had to have another ‘small circle’ such as QHF, (fig. 9), to allow the plane of the deferent itself to perform its own seesawing. And once more it was the same Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī who first developed his ‘Couple’ in order to account for that motion without creating a wobbling longitudinal effect.

Figure 9, not done to scale, gives a glance of the arrangement al-Ṭūsī was thinking about and that is now called the Ṭūsī Couple. The Couple was now attached to the tip of the diameter C, which was supposed to replace the Ptolemaic circle QHF, and still produce the same seesawing effect of the deferent plane. Although he did not say so explicitly, one can imagine that Ṭūsī would have proposed a similar set of circles to be attached to the tip of the epicyclic diameter R in order to produce the similar seesawing effect for the plane of the epicycle.

In sum, the Ptolemaic latitudinal motion of the five planets introduced new inconsistencies that were not introduced in the longitudinal motion. Here we have, in addition to a motion along ‘small circles’ requiring their own equants, fresh incomplete motions, like seesawing that could not be conceived within the same Aristotelian cosmological framework which required all motions to be uniformly circular and carried out by rigid spheres moving along axes passing through their own centers.

Once all those problems with Ptolemaic astronomy became known, the challenge for the astronomers became very clear, namely, to create new mathematical constructions that could describe the same motions, account for the corrected observational values, and at the same time meet the more demanding requirements of Aristotelian cosmology. Success in all those endeavours was not always easy to achieve, as we shall see, but the search for that success seems to have motivated Arabic theoretical astronomy throughout its history, producing as a result one alternative astronomy after another with varying degrees of elegance. Some of the mathematical results that were developed for the solution of the Ptolemaic problems such as the Ṭūsī Couple mentioned before, and the ʿUrḍī Lemma, which will be mentioned in the sequel, found their way to the Copernican alternative astronomy which deployed the same theorems for the same purposes in its own mathematical constructions.

Since the Almagest order of presentation of the Ptolemaic models was slightly changed in order to capitalize on the similarities of the techniques used for each model, or set of models, we shall follow the same change in order in surveying the alternative models that were developed in Islamic times to replace them. Thus we shall begin with the model for the Sun and follow it immediately with the model for the upper planets on account of the similarities inherent in the two models. Then the two similar models of the Moon and Mercury will be presented last.

Since there were many astronomers who participated in creating these alternative models at various times of Islamic history, the thematic approach we are adopting here will also necessitate that we do not present the works of any one astronomer all at once. Rather we will move chronologically with the model under discussion in order to demonstrate how later astronomers, while treating the same set of phenomena connected with a specific planet or planets, were building on each other’s works in order to produce the solution for each of the models they were conceiving.

As was stated earlier, none of the two hypotheses proposed for the Sun by Ptolemy were free from cosmological problems. The eccentric hypothesis required a center of motion other than the Earth which was by definition at the center of the world. And the epicyclic one required a center of heaviness in the realm of the celestial ether where such terms could not be strictly used.

Astronomers working in the Islamic domain seem to have accepted Ptolemy’s argument, stating that since one had to violate the Aristotelian cosmology in any case, one ought to opt for the lesser evil and choose at least the simpler of the two hypotheses. By ‘simpler’ they only meant the one that required a smaller number of spheres, and one motion instead of two, namely, the eccentric hypothesis. No serious objection that we know of was ever raised to this criterion by any of the astronomers working within the Islamic domain.

Only the fourteenth-century astronomer ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn ibn al-Shāṭir (d. 1375), who worked as a timekeeper at the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus, found fault with Ptolemy’s argument, as well as with Ptolemy’s observational data for the solar model. According to Ibn al-Shāṭir, the problem inherent in the eccentric hypothesis could not be dismissed so easily. And as a ‘true’ Aristotelian, he insisted that at least that aspect of the Aristotelian cosmology should be saved. That line of thought immediately led to the same predicament that was first faced by Apollonius and then by Ptolemy, namely, if not an eccentric hypothesis then what? The only other alternative they both perceived to be mathematically equivalent was the epicyclic one, and that involved more spheres and more motions, besides introducing a new cosmological problem of its own.

For Ibn al-Shāṭir, the issue of simplicity was not to supersede the cosmology, and thus if one could find a cosmological justification for the epicyclic hypothesis one ought to go along with it despite its relative complexity. In his attempt to find that justification, Ibn al-Shāṭir noted that Aristotle himself was not quite clear on the issue of the celestial bodies and the epicycles that could be included amongst them. For although one could agree with those who objected to epicycles in the celestial realm, on account of their introduction of centers of heaviness in that realm, one still had to question the Aristotelian assumptions themselves before committing oneself to adhere to either hypothesis.

Ibn al-Shāṭir argued as follows: We know that the celestial realm contained fixed stars, planets, and spheres, and now epicycles that caused the various motions we see from the Earth which was admittedly placed at the center of the world on account of its heaviness. But we also know from Aristotle that all those objects in the celestial realm were made of the same element ether. And yet we see certain parts of that celestial realm, namely, the stars, emit light, while other parts like the planets, receive light, and others like the bodies of the spheres themselves emit no light whatsoever. His conclusion was to say that even Aristotle will have to admit that there must be some composition in the celestial realm, and that it cannot all be made of the simple fifth element ether which was proposed by Aristotle.

A corollary of that is to say since there was some form of composition in the celestial realm, then that same composition could include the bodies of the epicyclic spheres that were, on the whole, much smaller than most of the fixed stars that we know were out there in the celestial realm emitting light and contributing to the celestial composition. Hence opting for the epicyclic hypothesis, despite its complexity, would at least be defensible on some Aristotelian grounds, while the eccentric hypothesis was not.

The upshot of the argument was to say that one can introduce in the mathematical models describing celestial motions as many epicycles as one needed to have since all of them would be subject to the same reasoning. As a result, all the models proposed by Ibn al-Shāṭir for the various planetary motions were all strictly concentric, actually geocentric, but deployed more epicycles in order to make up for that concentricity.

In the case of the Sun, however, Ibn al-Shāṭir had other objections to make, namely observational ones. For he had found that, according to his own observations of eclipses and the like, the apparent size of the solar disk did not remain to be equal to \(0^{\circ}31^{\prime}20^{\prime\prime}\) at all times as was stated by Ptolemy. Instead, it seemed to be as large as \(0^{\circ}36^{\prime}55^{\prime\prime}\) while at perigee, and as little as \(0^{\circ}29^{\prime}5^{\prime\prime}\) at apogee, while it was \(0^{\circ}32^{\prime}32^{\prime\prime}\) at mean distance. These results could not be accounted for by either of the two hypotheses proposed by Ptolemy for the Sun.

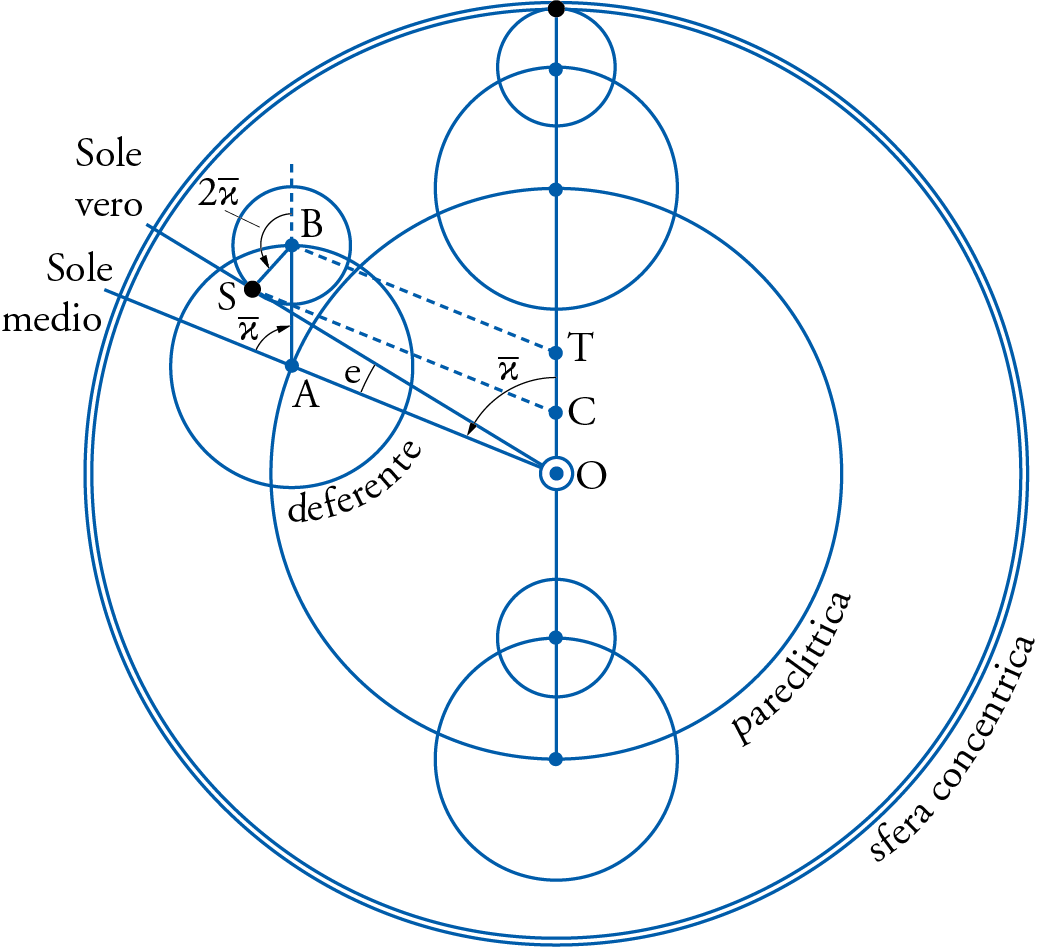

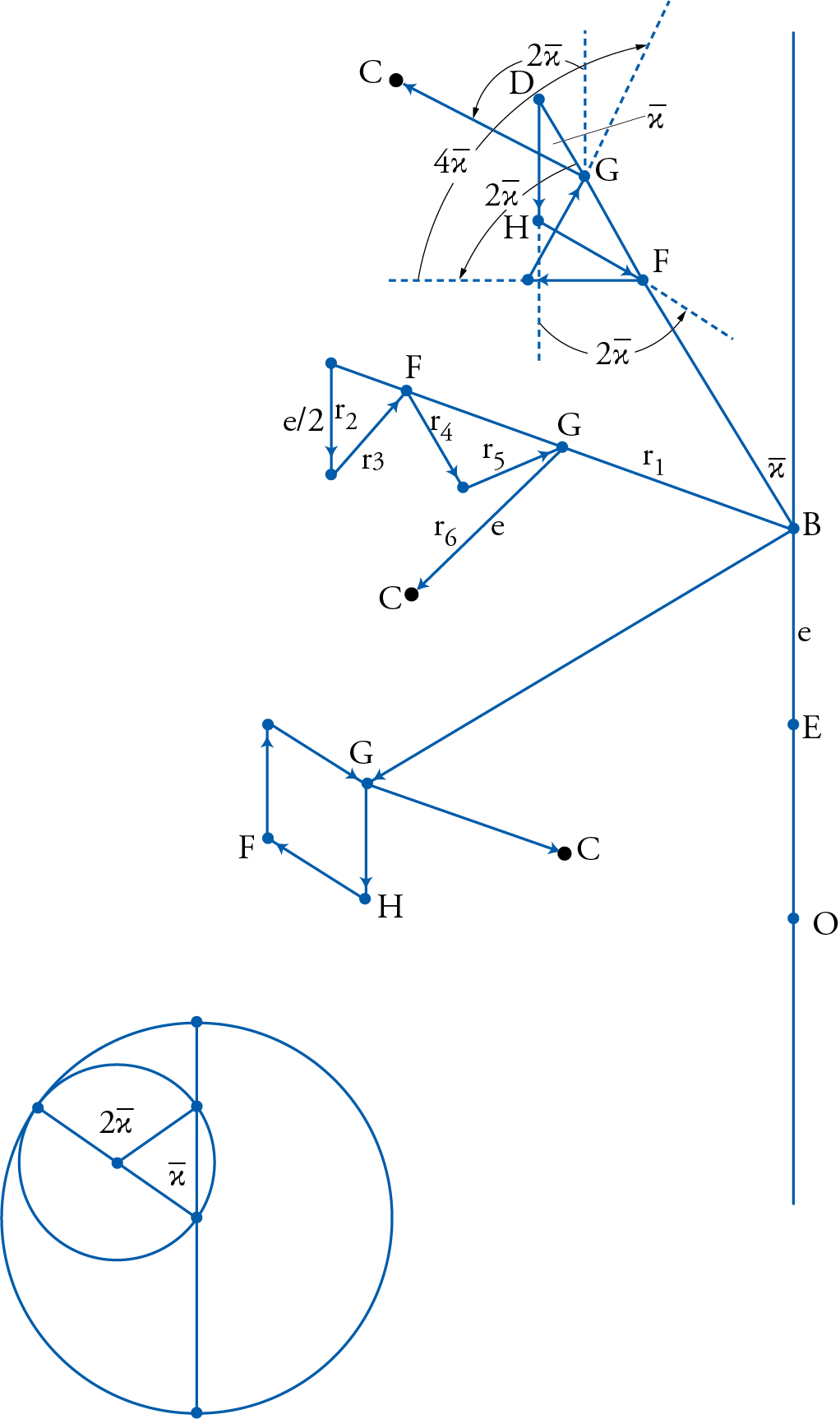

Instead Ibn al-Shāṭir proposed his own model (fig. 10), which had the following elements. For an observer at point O, the Sun seemed to be moved by a set of spheres constituted of the following:

- An all-encompassing sphere, concentric with the Earth, that moved the solar apogee in the direction of the succession of signs by about 1°/60 Persian years.

- A parecliptic sphere, immediately below the first, also concentric with the Earth, of radius 60 parts that moved the Sun in the same direction as before by its mean daily motion.

- A deferent sphere carried by the parecliptic sphere as an epicycle, of radius 4;37 parts of the same parts that made the radius of the previous sphere 60 parts. The deferent moved in the direction opposite to that of the succession of the signs but at the same speed as the parecliptic.

- Finally, the Sun was moved by a small epicycle of its own, with center B, in the direction of the succession of the signs at a speed equal to twice the speed of the daily mean motion of the Sun that was carried by the deferent itself.

With this arrangement Ibn al-Shāṭir managed to account for all the observational results he just cited for the apparent solar disk, as well as the solar equation which he also found to be at variance from the equation given by Ptolemy.

It should be immediately obvious that the kinematic effects of this model allowed Ibn al-Shāṭir to use an application of the Apollonius equation that was used earlier, in order to replace the eccentricity OT with a mathematically equivalent epicyclic deferent whose radius AB was equal and parallel to it, as was the radius of the solar epicycle equal and parallel to the eccentricity in the Apollonius equation.

The addition of the smaller epicycle with center B, allowed Ibn al-Shāṭir to use another theorem, namely, the ʿUrḍī lemma which will be discussed below, to introduce the equivalent of an equant, here designated as point C, without having to suffer from the cosmological absurdities of the analogous Ptolemaic equant used for the upper planets. In addition, it allowed him to assign the new eccentricity OC, a value of 2°7′, arrived at by his own observations, thus producing a new maximum solar equation of \(2^{\circ}2^{\prime}6^{\prime\prime}\) that was also confirmed by his own observations.

In this model, point C becomes the apparent center around which the Sun seems to move at uniform speed, while in reality it was moved around by several spheres, each one of them moving uniformly about an axis passing through its own center.

As was stated before, the main problem with Ptolemaic astronomy was its reliance on the feature of an equant which was used to account for the observational variations in planetary motions. Not only professional astronomers, but apparently philosophers as well, knew of this problem. Strangely enough, the first attempt to create alternatives for it that we know of came from the latter’s circles. Specifically, it was Abū ʿUbayd al-Jūzjānī (d. 1070), a student of Ibn Sīnā (Avicenna, d. 1037), who was the first to mention that such a problem had been discussed in the circle of Avicenna, and that Avicenna himself had already found a solution for it, but was not going to tell his student about it in order to encourage the student to find a solution on his own. The same student went on to say that he did not think his master had done so and that he was the first to produce such a solution.

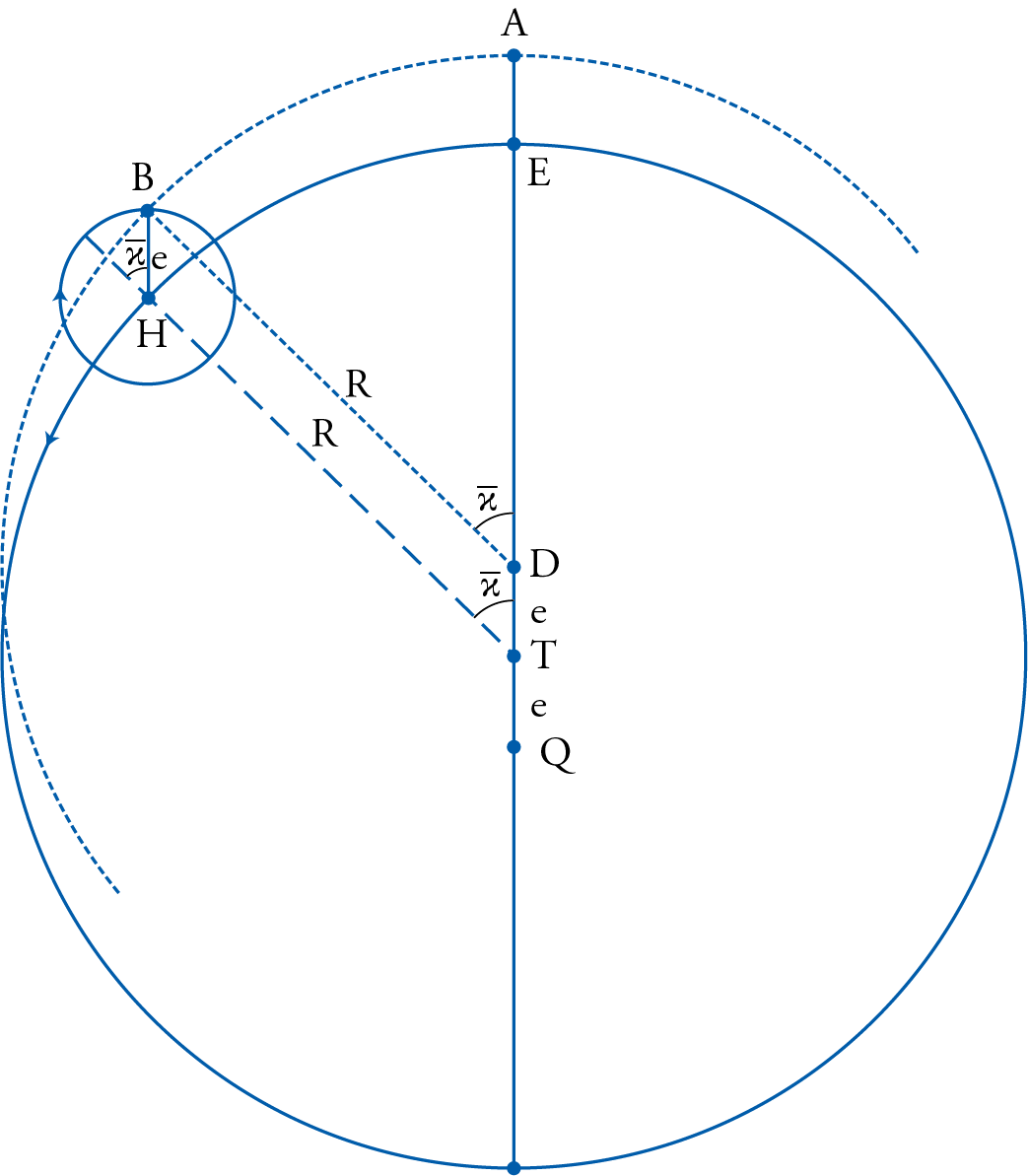

In fig. 11, al-Jūzjānī proposed to solve the problem of the equant with a rather naïve application of what we have been calling the Apollonius equation. With an observer at the center of the world at point Q, and a deferent with center T, al-Jūzjānī proposed to replace the equant point D with an epicycle drawn at the circumference of that deferent at point H with radius HB, equal to the eccentricity TD. The order of motion and the arrangement of the spheres were analogous to the arrangement and order that were used by Ptolemy in the case of the double hypotheses for the Sun when using the Apollonius equation.

In effect, al-Jūzjānī’s arrangement would indeed translate the mean uniform motion from the fictitious point D to the center of a real epicyclic center H. But what it also did was to translate the whole deferent itself by making the center of the planetary epicycle now move along the dotted circle AB, rather than the original deferent EH stipulated by Ptolemy. Had the deferent been as fictitious as the equant, this arrangement would have worked. But the truth of the matter is that the Ptolemaic deferent had an observational reality and could not be simply translated without suffering serious consequences. It was such considerations, I think, that moved the fourteenth-century astronomer Quṭb al-Dīn al-Shīrāzī (d. 1311) to judge al-Jūzjānī, on the basis of this attempt, to have disgraced himself (faḍaḥa nafsahu).

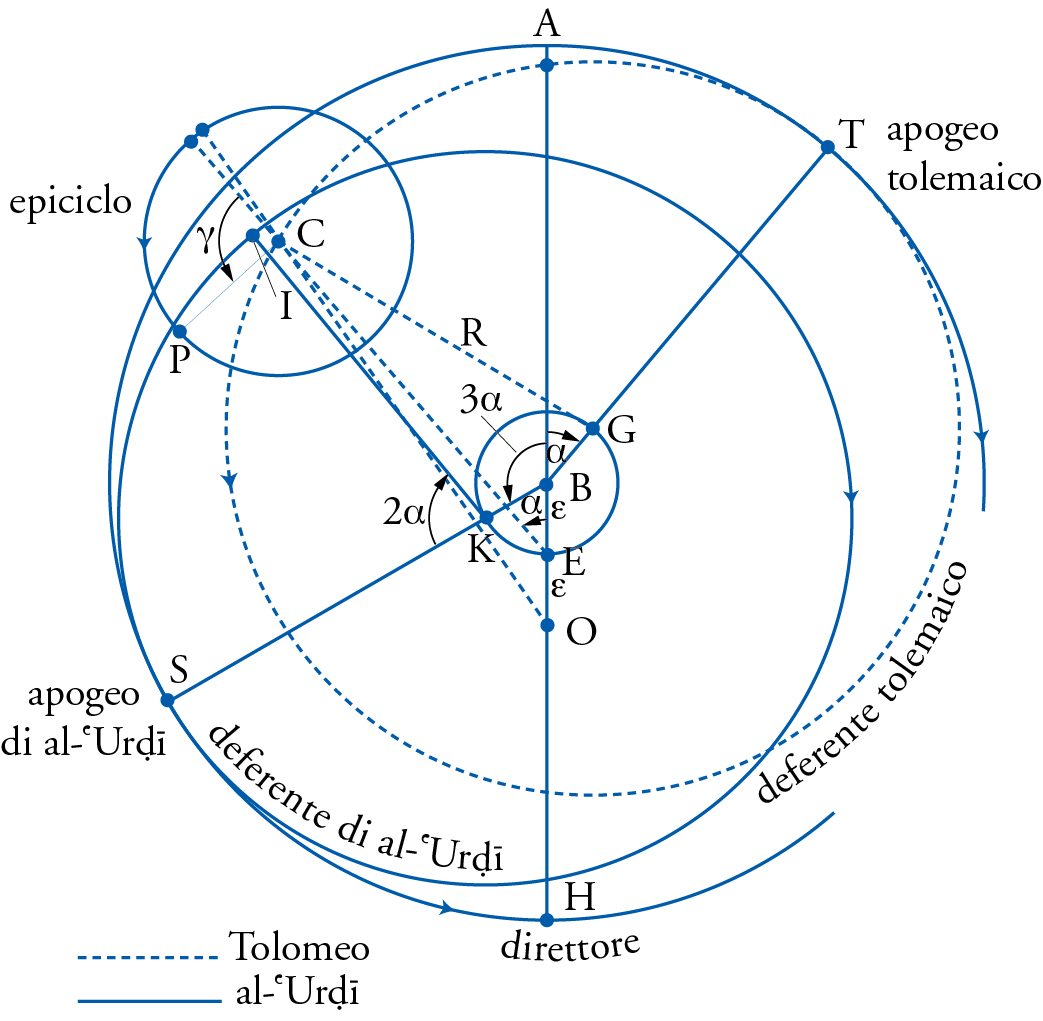

The next serious astronomer to attempt a more successful solution of Ptolemy’s equant problem was the Damascene astronomer Muʾayyad al-Dīn al-ʿUrḍī, who lived during the first half of the thirteenth century. At one point toward the end of his life, and obviously after establishing his fame as a serious astronomer and engineer of scientific instruments, he was called upon by the equally famous astronomer Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī, mentioned above, to take charge of designing and building the instruments for an observatory that was founded in 1259 by al-Ṭūsī in the city of Marāgha in northwest modern-day Iran. The association of these two men at this Marāgha observatory, together with the students and associates who joined them there, constituted one of the most fertile periods in the history of Arabic astronomy.

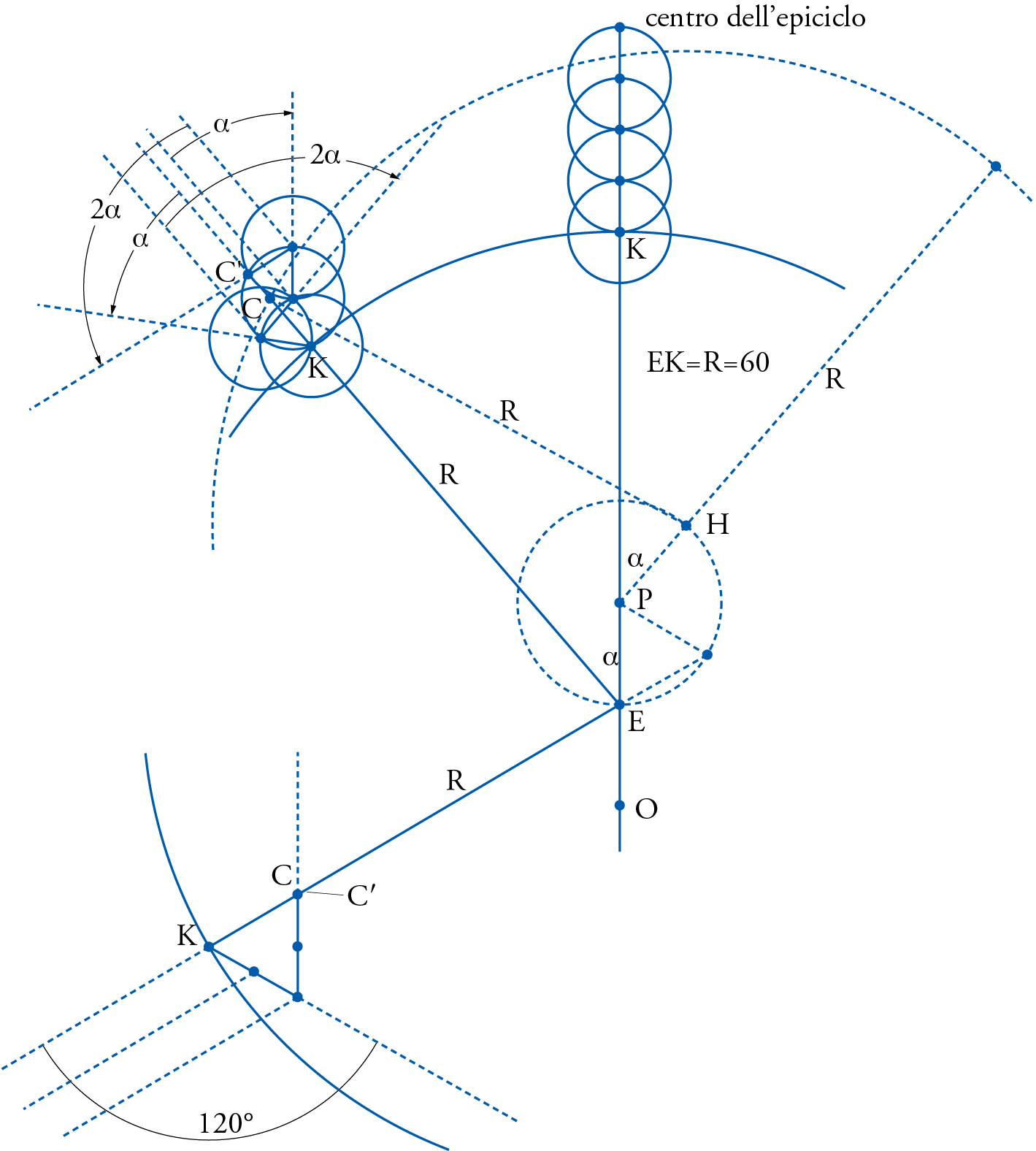

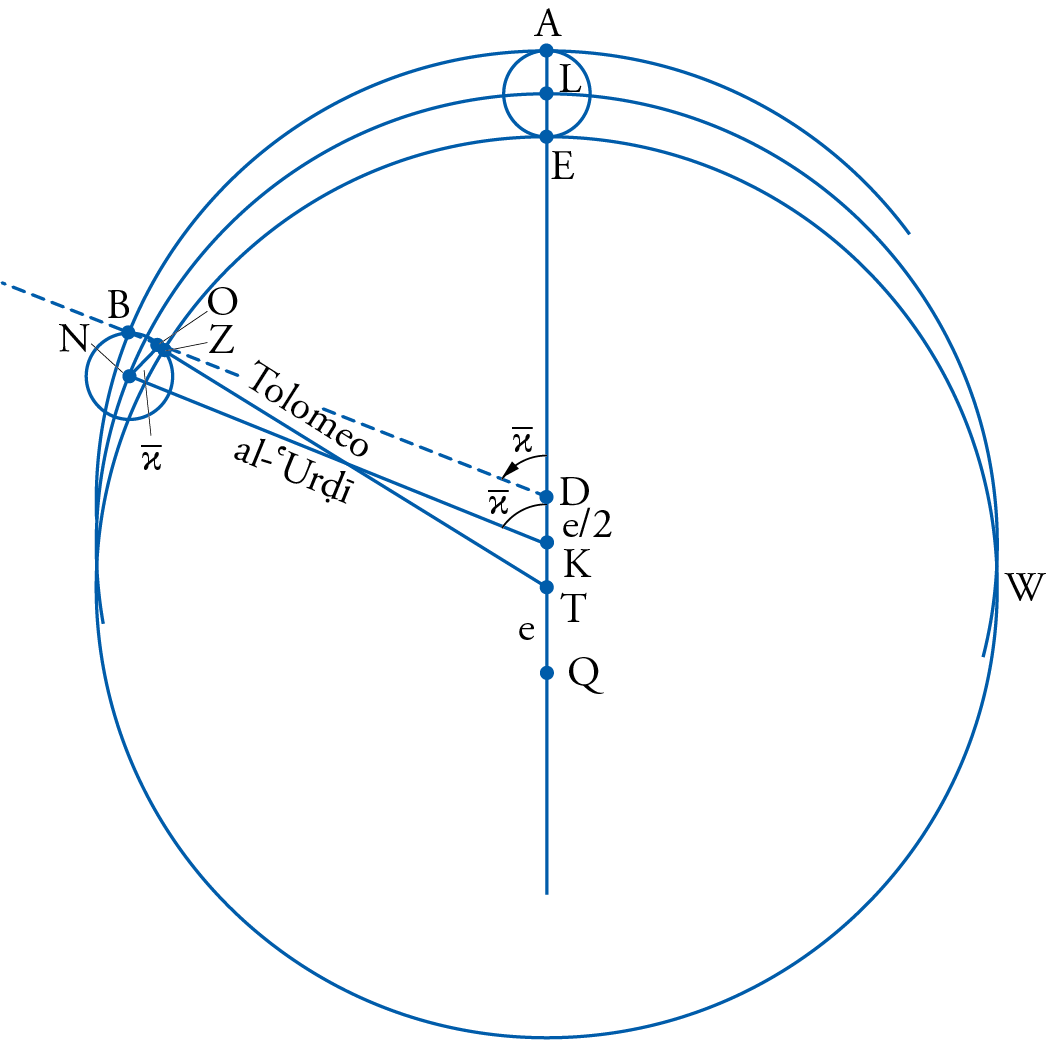

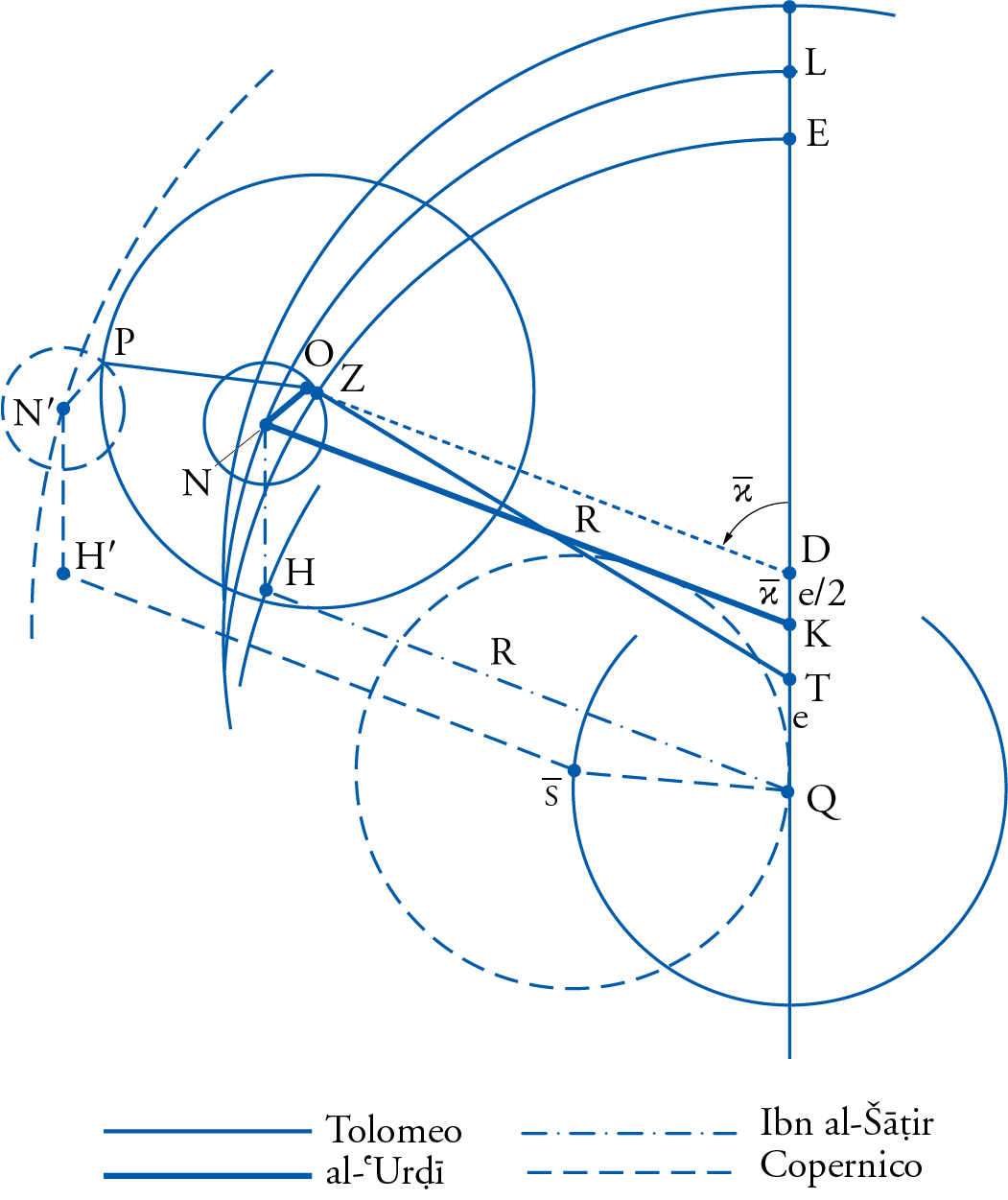

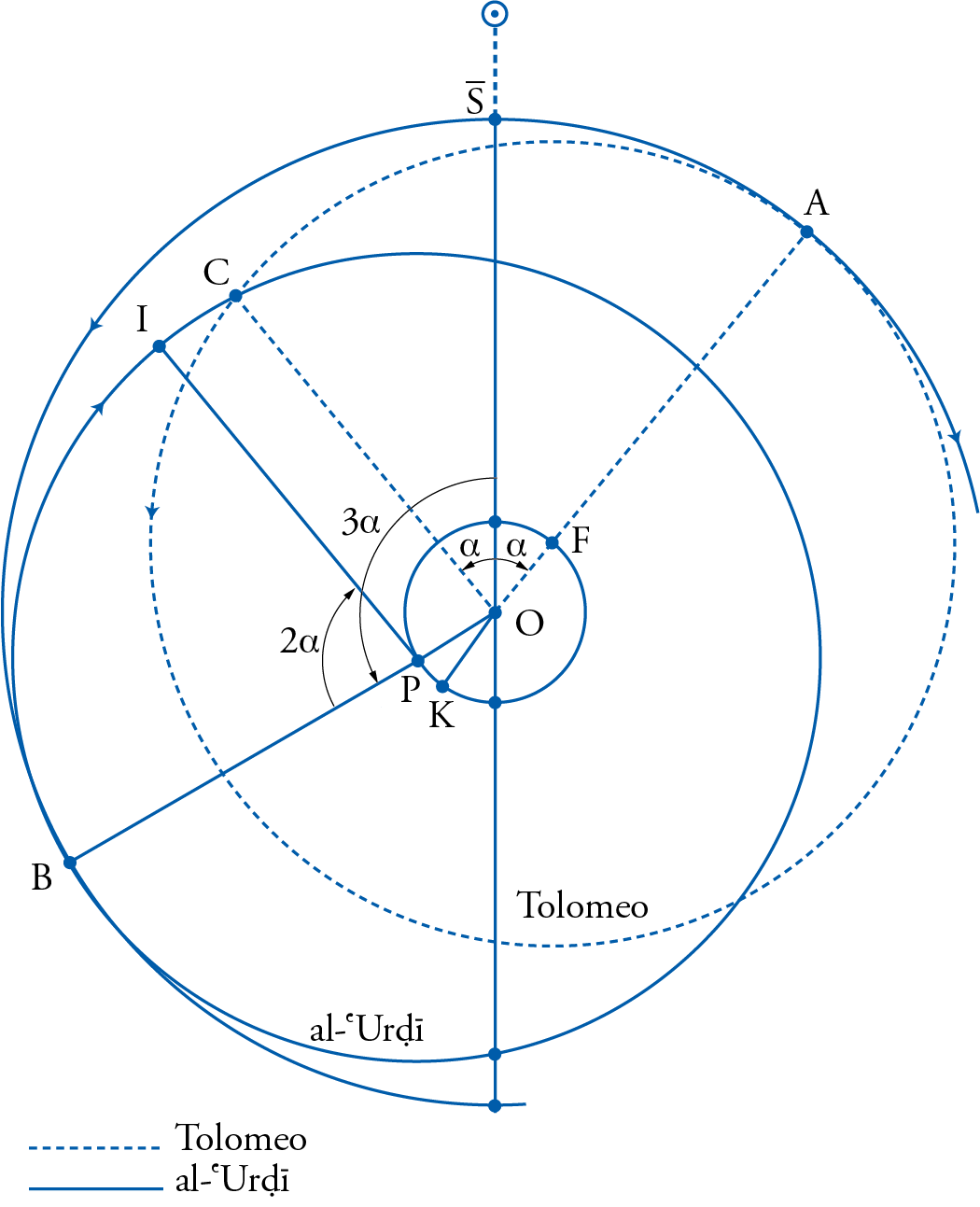

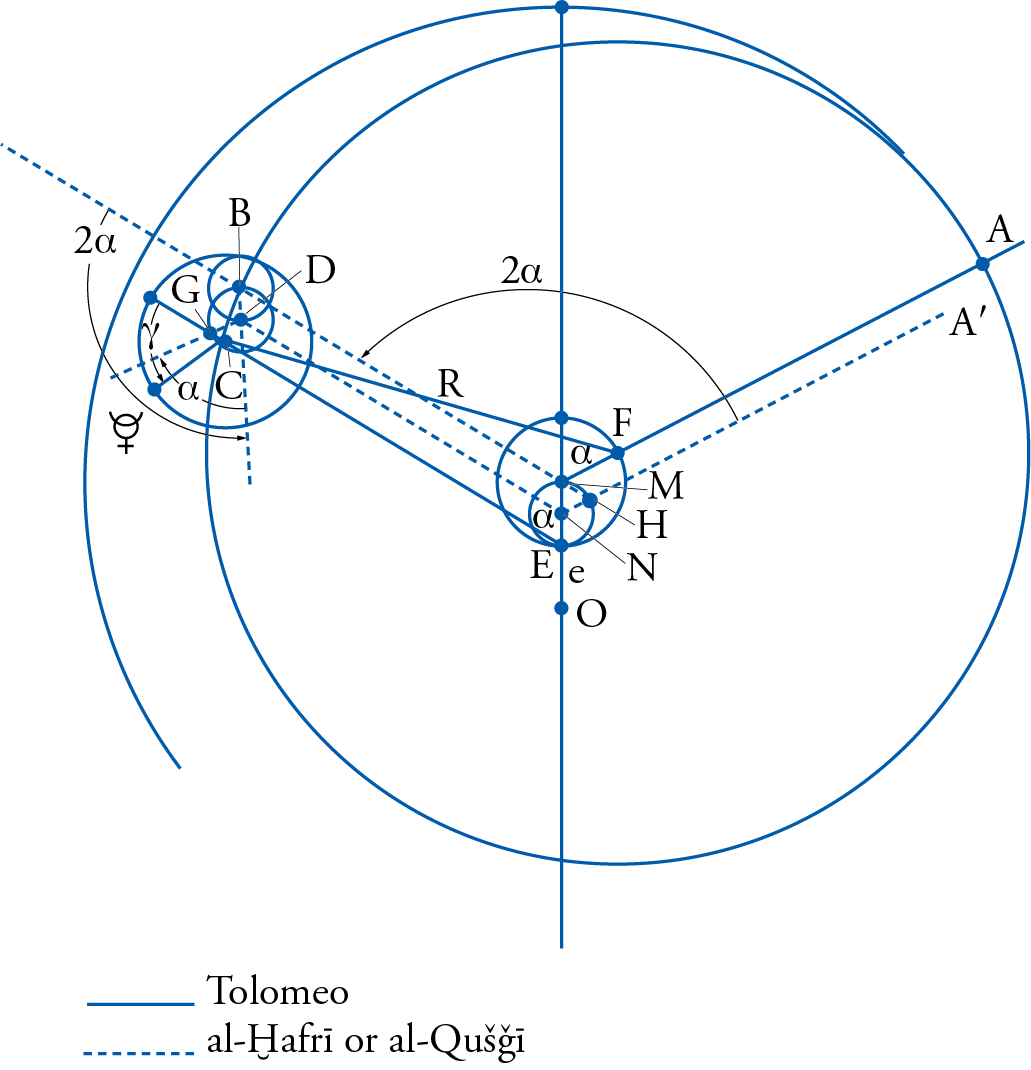

In a text devoted to the complete revamping of Ptolemaic astronomy, simply called Kitāb al-Hayʾa (Book on Astronomy), which was completed before joining the Marāgha observatory (he complained in that text that he did not have any observations to base his theories upon), al-ʿUrḍī proposed for the upper planets a mathematical model which would do away with the cosmological and physical absurdities of the Ptolemaic model for those planets. In effect, what he proposed to do was to introduce into the Ptolemaic model a new deferent now centered on point K in fig. 12, with the same radius R as the Ptolemaic deferent, and allowed it to move around its own center K at the same mean motion of the planet as the motion stipulated by Ptolemy to take place around the equant D. Now, he allowed that deferent to carry a small epicyclet, here designated with center N, to move also in the same direction and at the same speed around its own center N thus bringing the radius NO, which was first pointing towards K, to make an angle with NK equal to the same mean motion of the planet as pointed on the diagram. He then attached the center of the Ptolemaic epicycle to point O on the small epicyclet. Then al-ʿUrḍī stated that the combined motion of just those two spheres would make point O, on the circumference of the small epicyclet, come very close to point Z, which was originally the center of the Ptolemaic epicycle for Ptolemy. In fact, the two points would be so close as to become identical along the line of apsides and indistinguishable in between.

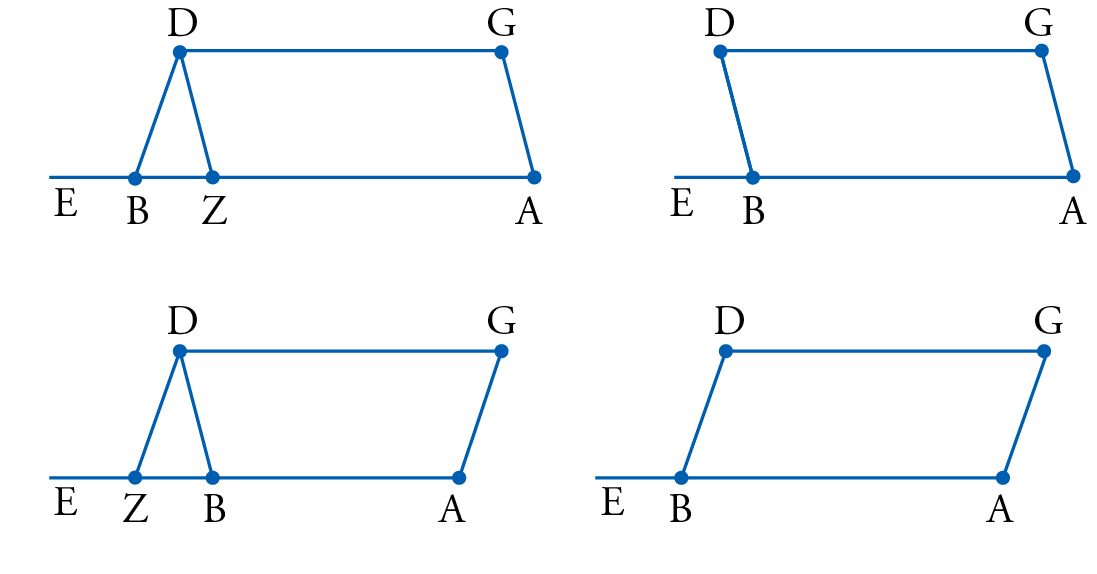

Although that arrangement would take care of the physical absurdity of the equant – for now both spheres, the new deferent and the epicyclet, would move uniformly around their own respective centers – there remains to demonstrate that the motion of point O, which was after all the center of the planet’s epicycle and now very close to point Z, would also indeed appear to move at the same uniform motion with respect to the equant point D, a phenomenon which had an observational reality that could not be bypassed. In order to supply that demonstration, al-ʿUrḍī developed his own mathematical theorem, now dubbed the al-ʿUrḍī Lemma, fig. 13. In it he simply demonstrated that any two lines AG and DB, that are equal in length, when they are placed on line AB such that they make equal angles with that line either internally or externally, then the line DG joining their extremities will always be parallel to line AB. Applied to his model, he could then prove that line DO will always be parallel to line NK, and angle ODE, which was the angle of mean motion in the Ptolemaic model, would be equal to the alternate angle NKD which designates the speed of the new deferent. This way al-ʿUrḍī managed to account for all the motions in the Ptolemaic model without having to make the assumption of the physically absurd equant.

In fact, the success of this model attracted the attention of the same al-Shīrāzī, mentioned earlier, who adopted it as his preferred model in his own works Nihāyat al-idrāk and Tuḥfat al-shāhiyya, which he wrote as commentaries on his own master’s astronomical masterpiece, al-Ṭūsī’s al-Tadhkira fī ʿilm al-hayʾa (Memoir on Astronomy). Furthermore, the very same technique of bisecting the eccentricity as was done by al-ʿUrḍī was also used some three hundred years later by Copernicus, who adopted it for the same model in his own astronomy. However, he left the final demonstration unproven and it was later taken up by Maestlin in a correspondence with his own student Kepler.

We already had occasion to examine Ibn al-Shāṭir’s model for the Sun, and the arguments that were made in its favor. Here we shall see an additional feature of that model, namely, that it did not only succeed in solving both the observational as well as the cosmological problems of Ptolemy’s model for the Sun, but that it could also be generalized to solve the motions of all the other planets, except Mercury where it needed a slight modification. Thus his models for the upper planets and the Moon were essentially the same as the one he used for the Sun, with the appropriate adjustments for dimensions and motions, of course.

In fig. 14, whose main features are similar to those of the solar model, Ibn al-Shāṭir used those same features to represent the motions of any of the upper planets. Taking Saturn as an example, Ibn al-Shāṭir stipulated the following spheres and motions for that planet:

- The first sphere called the ‘encompassing sphere’ which is not represented here, moved at the same rate as the motion of the other planetary apogees.

- The second sphere, called the ‘inclined sphere’, represented here by its radius QH, was also concentric with the observer at the center of the world Q, and moved in the order of the succession of the signs at the same rate as the mean motion of the planet. Since this sphere belonged to an upper planet Saturn its inclination was fixed at 2;30°.

- The third sphere, called the ‘deferent’, moved in the opposite direction from the first and at the same speed, thus making HN always parallel to QD by the Apollonius equation. In the case of Saturn the radius HN of this sphere was taken as 5 1/8 parts in the same parts that make the radius of the inclined sphere 60 parts.

- The fourth sphere was called the ‘director’, represented here by a radius NO which was equal to 1;42,30 parts in the same parts as before. It moves in the order of the succession of the signs at the same speed as the previous two spheres.

- The fifth sphere, whose center was at point O, was the usual epicyclic sphere of the planet and is not represented here for it was the same as the Ptolemaic epicycle. The body of the planet was embedded in this last sphere and was moved by its anomalistic motion.

From the dimensions given for the planet Saturn we can conclude that HN, which was given as 5 1/8 parts was in fact equal to 5;7,30 parts and thus equal to \(3e/2\), where e was the Ptolemaic eccentricity 3;25 parts for Saturn. The small director had the dimension 1;42;30, which was exactly half the Ptolemaic eccentricity. So, the dimensions given in the diagram of \(3e/2\) for HN and \(e/2\) for NO, could apply to all the upper planets, each according to the eccentricity it had in the Ptolemaic version.

The advantage of Ibn al-Shāṭir’s model over that of Ptolemy is obvious. For now, he did not only dispense with the eccentrics, but made all spheres move at uniform speeds about axes passing through their own centers, thus dispensing as well with the physical absurdity resulting from the Ptolemaic equant. Needless to say that his model also accounted for the same observations as the ones used by Ptolemy.

On the technical side, when examined closely, Ibn al-Shāṭir’s model reveals the use of two theorems already described above. The first was the theorem we have been calling the ‘Apollonius equation’, which accounts for the equation between the motions along an eccentric centered at K and a concentric with an epicycle whose radius HN is equal to the eccentricity QK. The second theorem was al-ʿUrḍī’s lemma, here represented schematically by the dotted parallel lines DO and KN, as was the case in al-ʿUrḍī’s model. Through that parallelism, and the motions producing it, point O was brought to coincide with the Ptolemaic center of the epicycle Z along the line of apsides, and to be indistinguishable from it at other places, thus preserving the effect of the Ptolemaic deferent. It also made point O seem as if it were moving uniformly around the Ptolemaic equant D, which was also required by the observations, while in fact it moved like all the other points about axes that pass through the centers of the spheres producing the motion. In that sense one can describe Ibn al-Shāṭir’s model as an improvement over that of al-ʿUrḍī, and like the latter it also avoided the absurdities of the Ptolemaic model.

Moreover, the same construction developed by Ibn al-Shāṭir, turned out to be technically equivalent to the one used by Copernicus to account for the motion of the same upper planets as is evident from fig. 15. The only exception is that in the case of the Copernican model, represented here with dashes, the mean Sun was held fixed while the Earth was made to move. All other features remained the same as is evident from the parallel vector-like lines leading to the position of the planet P in all four models represented in the diagram. Only the last three are free from the Ptolemaic problems, although the heliocentricity of Copernicus introduced another Aristotelian cosmological problem of its own for Copernicus’s time.

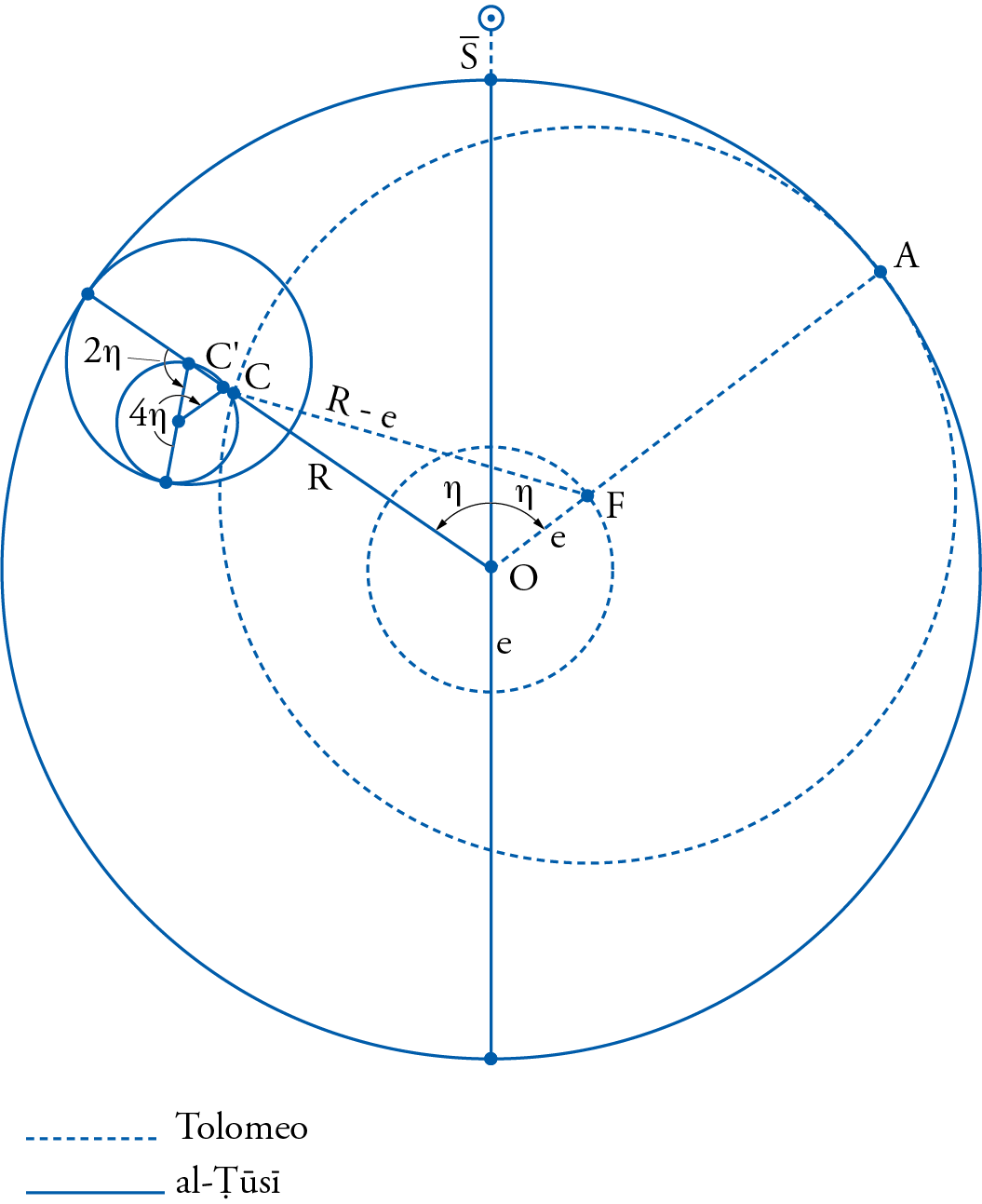

We had seen earlier that Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī had already developed his own mathematical theorem, now called the ‘al-Ṭūsī couple’, in order to avoid the problems of the Ptolemaic planetary motions in latitude. In essence his theorem demonstrated that a combination of uniform circular motions could in fact produce an oscillatory linear motion. As we have seen he had already stated the main principles of that finding in the context of his commentary on the Ptolemaic text of the Almagest in 1247. A few years later he apparently began to realize the full power of this theorem, and realized he could use it in other cases as well, mainly where one needed a point to move around a center of a sphere but at the same time be allowed to move closer to that center and to recede away from it wherever that was needed. One ideal case for using such a theorem was in the case of the Moon, as we shall soon see, where the crank-like construction invented by Ptolemy allowed the very same phenomenon to take place, namely, allow the center of the epicycle to come closer to the Earth so that the epicycle would appear larger and thus produce a greater angle for the epicyclic anomaly at quadrature and then recede away from the Earth at the syzygies.

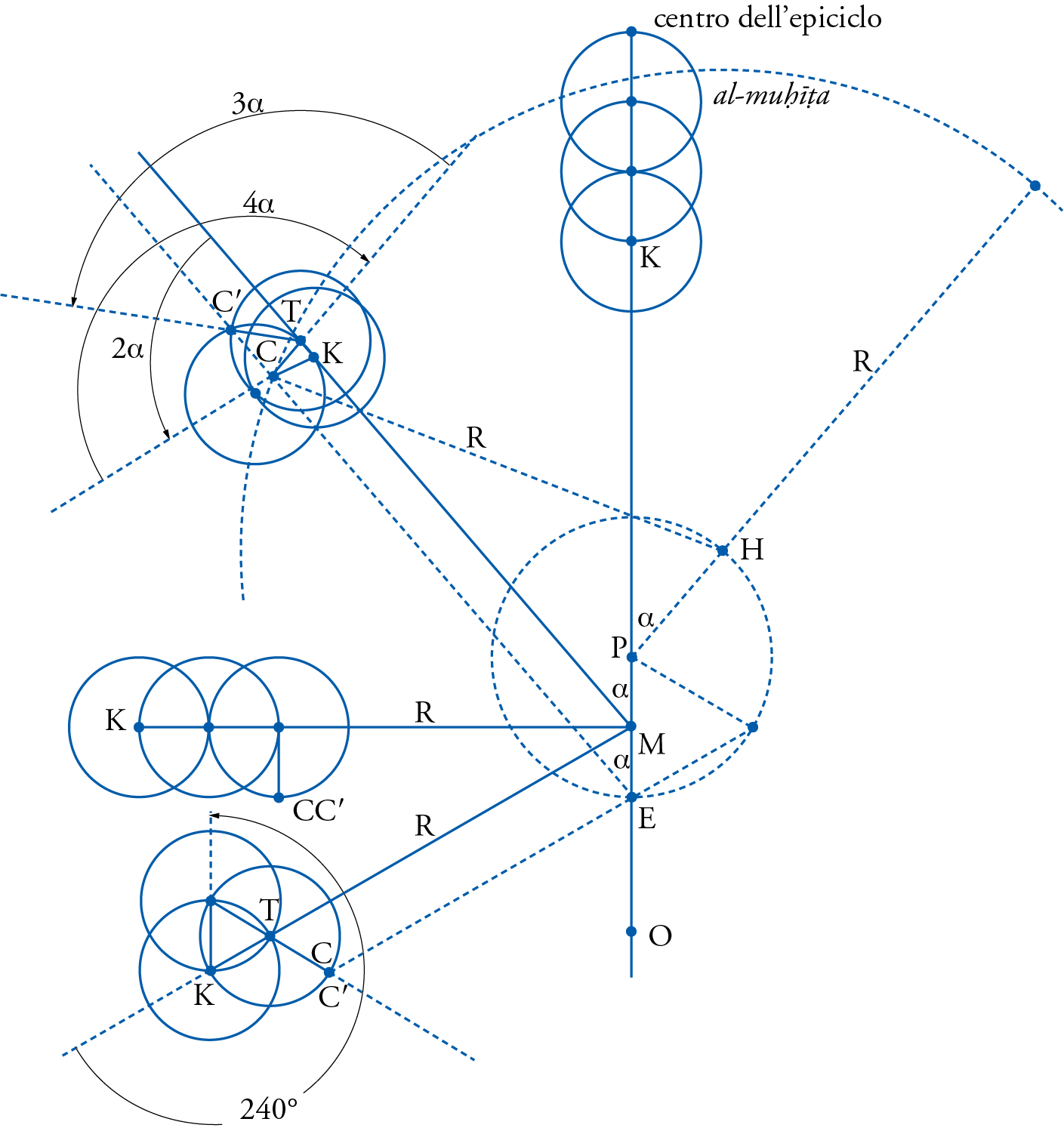

In the case of the upper planets, al-Ṭūsī saw that he could use the same theorem in order to resolve the problem of the Ptolemaic equant. In fig. 16, he exchanged the Ptolemaic deferent for a new sphere now centered on the equant D. Then at the cincture of that sphere he mounted al-Ṭūsī couple first located at the apogee A, as in the diagram. Then he allowed the larger of the spheres of the couple to move at the same speed as the deferent, which was itself equal to the mean motion of the planet and in the same direction, and the smaller sphere to move at twice that motion in the opposite direction. The effect of the couple would then allow the point of inner tangency of the two spheres to oscillate along the axis of the larger sphere of the couple, reaching point C, when in the general position shown in the diagram. This point C was so close to the Ptolemaic center of the epicycle Z, that the dotted circle it traced was, for all practical purposes, identical with the Ptolemaic deferent.

The advantages of this model are that it preserved the observational basis of the Ptolemaic model by preserving the deferent, but allowed the center of the epicycle C, now very close to Z, due to the linear oscillatory motion produced by the al-Ṭūsī couple, to move uniformly about the center of its own sphere, which in turn moved about the center of its own sphere as well. Thus the only cosmological problem remaining would then be that of the eccentricity which is now taken to be twice as that of Ptolemy. But, as we have seen before, it was only Ibn al-Shāṭir who made a big issue of the eccentrics. The others accepted them, probably always knowing that they could compensate for them with an epicyclic model like the Apollonius equation if need be, as was indeed done by Ibn al-Shāṭir.

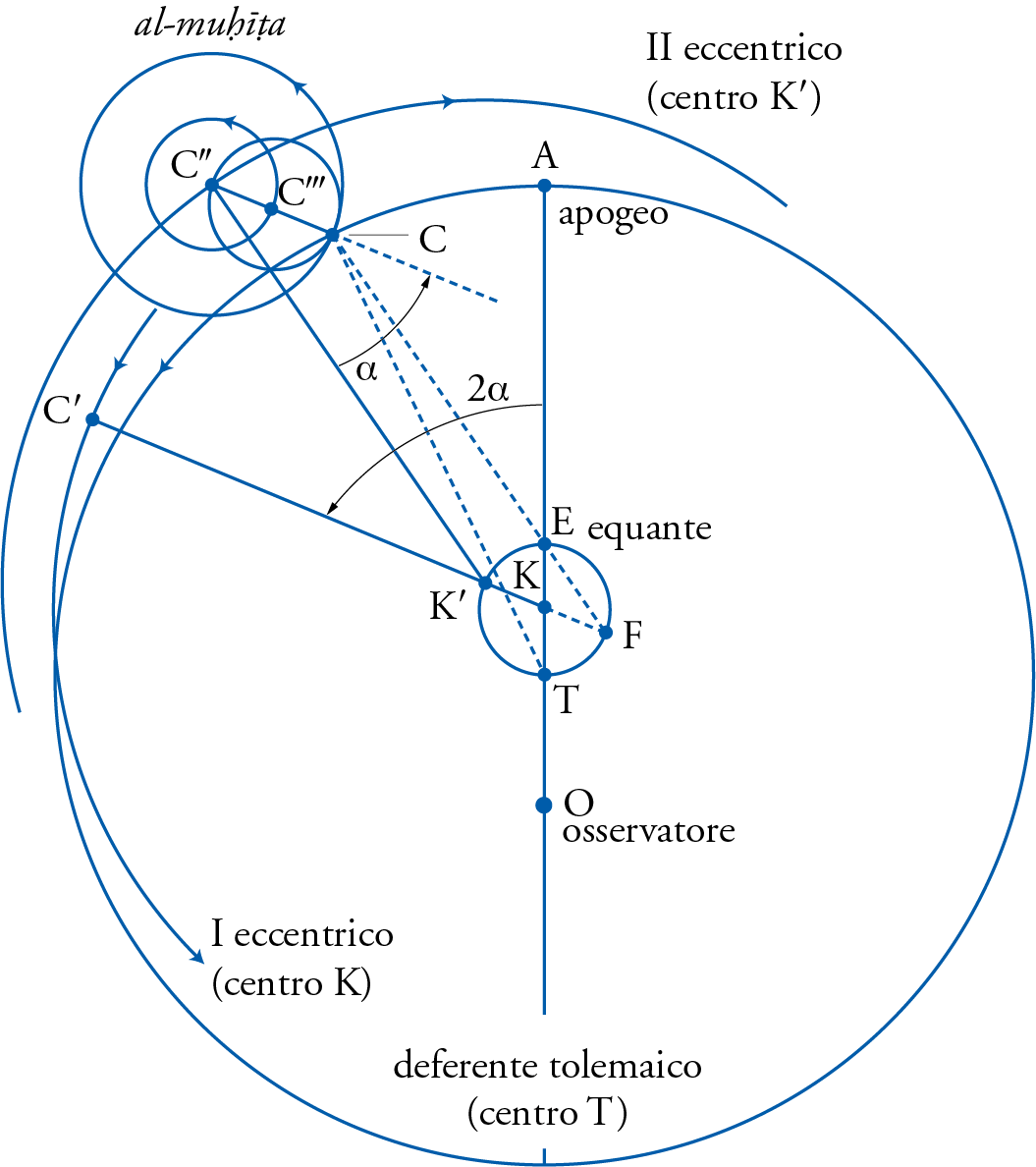

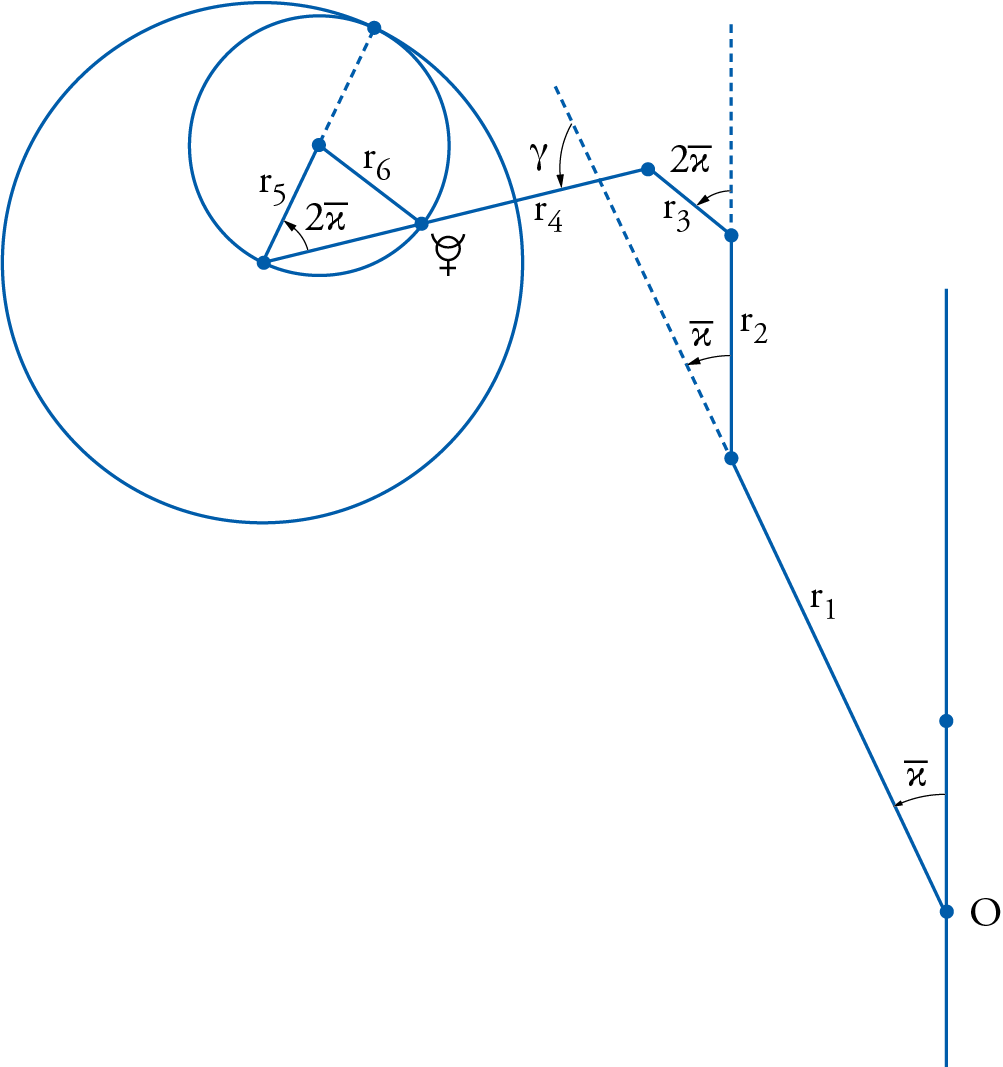

In his attempt to account for the same observational results already reached by Ptolemy, by preserving both the deferent and the equant, Shams al-Dīn al-Khafrī (d. 1550) built on the experience of earlier astronomers, especially al-ʿUrḍī as we shall soon see, to construct a model made up of several new spheres whose motion remained strictly about axes that passed through their centers. Their combined motions would make the center of the epicycle \(C^{\prime\prime\prime}\) (fig. 17) seem as if it was moving along the Ptolemaic deferent and at a uniform speed about the Ptolemaic equant. His structure required of course several applications of the al-ʿUrḍī lemma discussed above.

In the same fig. 17, al-Khafrī introduced a new deferent similar to that of al-ʿUrḍī in that it shared the same center as that of al-ʿUrḍī at point K, thus bisecting the Ptolemaic eccentricity, also like al-Khafrī’s own contemporary Copernicus. Then he allowed that new deferent to move at the same speed as the mean motion of the planet and in the same direction, thus bringing the center of the epicycle from the point of apogee A to point \(C^{\prime}\). Al-Khafrī then postulates the existence of another eccentric now centered at point \(K^{\prime}\), with \(KK^{\prime}= e\), also half the Ptolemaic eccentricity, a technique quite similar to the one used by al-ʿUrḍī for the Moon as we shall soon see. The second eccentric was then allowed to move in the opposite direction from the first, i.e., in the direction opposite to that of the succession of the signs, at twice the speed of the planet’s mean motion. This in effect brings point \(C^{\prime}\) to position \(C^{\prime\prime}\).

At that point al-Khafrī had two options, both of them leading to the same result. He could either have an epicyclet with a radius equal to the full Ptolemaic eccentricity (called al-muʾaṭṭa by the same al-Ṭīrāzī mentioned before and here followed by al-Khafrī), or have two smaller epicyclets with radii equal to half the eccentricity but their diameters in line with one another and only the first was allowed to move. In both options the motion was stipulated to be the same as that proposed by al-ʿUrḍī for his own epicyclet, namely, that it was to move at the same speed as the mean motion of the planet, and in the direction of the succession of the signs.

The effect of all these motions was to bring point \( C^{\prime\prime\prime} \), which was supposed to be lying along line \(K^{\prime}C^{\prime\prime}\) to come very close to the Ptolemaic epicyclic center C, so close that even a skilled observer could not observe the difference between them as al-ʿUrḍī would say. It was obvious then that point \( C^{\prime\prime\prime}\) would now hug the Ptolemaic deferent and thus save that part of the observations. Then it could be easily demonstrated, by the application of the al-ʿUrḍī lemma to lines \(E C^{\prime\prime\prime}\) and \(K^{\prime}C^{\prime\prime}\) that can now be shown to be always parallel, that point \(C^{\prime\prime\prime}\) will also seem to move uniformly around the Ptolemaic equant E, thus saving the other portion of the observations.

As was already stated while surveying the Ptolemaic models, the lunar motions exhibit features that are much more complicated than those of the upper planets. In order to account for those motions, Ptolemy had to introduce a crank-like arrangement in addition to the two hypotheses of the eccentric and the epicyclic. But we have also seen that this new arrangement also introduced its own problems and cosmological contradictions. As far as we know, the first person who seems to have succeeded in resolving some of the problems in the Ptolemaic model was the same Muʾayyad al-Dīn al-ʿUrḍī, mentioned before.

In fig. 18, where al-ʿUrḍī’s model is superimposed over that of Ptolemy, he introduced some dramatic modifications to the Ptolemaic model. He went as far as to say that the direction of motions in the Ptolemaic model ought to be (1) reversed, and (2) changed in quantity, in order to make things appear to behave the way Ptolemy found them to behave by observation. Al-ʿUrḍī now proposed an inclined sphere that would move around the center of the world, in the direction of the succession of signs, at three times the speed of the elongation required by the Ptolemaic model, originally marked by angle \(\alpha\). Then al-ʿUrḍī’s new deferent sphere, with center P, instead of F as in the case of the Ptolemaic model, would now move back in the opposite direction, but uniformly around its own center, and at twice the speed only, rather than three times. The net result was to bring line PI to the same direction as line OC, thus making the center of the lunar epicycle, now carried at I, appear to have a mean motion in the direction of the succession of the signs by an amount equal to the elongation found by Ptolemy’s observations.

This way, al-ʿUrḍī did not only solve the problem of the lunar equant – for he now has the deferent moving uniformly on its own center rather than the center of the world – but also managed to solve the problem of the prosneusis point, for line PI, now connecting the center of the epicycle to the center of the deferent carrying it, will pass very close to the original prosneusis point K of Ptolemy, as it was supposed to do, and as is obvious from the diagram.

The al-Ṭūsī couple, which was first developed, as we have seen above, to solve some of the motions in planetary latitudes, was also used by al-Ṭūsī to solve some of the problems of the Ptolemaic lunar model. At least as far as the lunar equant problem was concerned, the new arrangement proposed by al-Ṭūsī came very close to answering that problem. In fig. 19, where al-Ṭūsī’s model (in continuous lines) is superimposed over the Ptolemaic one (in dotted lines), al-Ṭūsī made his deferent move around the center of the world at the same speed as the Ptolemaic elongation and in the direction of the succession of signs. Then, in order to allow the center of the epicycle \(C^{\prime}\), which is carried by that deferent, to move closer to the Earth and recede away from it in a linear motion, he allowed the al-Ṭūsī couple to fulfil that function. The resulting motion, as seen in the diagram, will indeed bring point \(C^{\prime}\) very close to C, the Ptolemaic epicyclic center.

Al-Ṭūsī’s model obviously took care of the lunar equant problem, and answered rather well the problem of variation in the epicyclic size for which Ptolemy had to introduce the crank-like mechanism spoken of earlier. But it left the prosneusis problem intact. For that, al-Ṭūsī had to resort to adjusting spheres placed around the epicycle itself, which are omitted here.

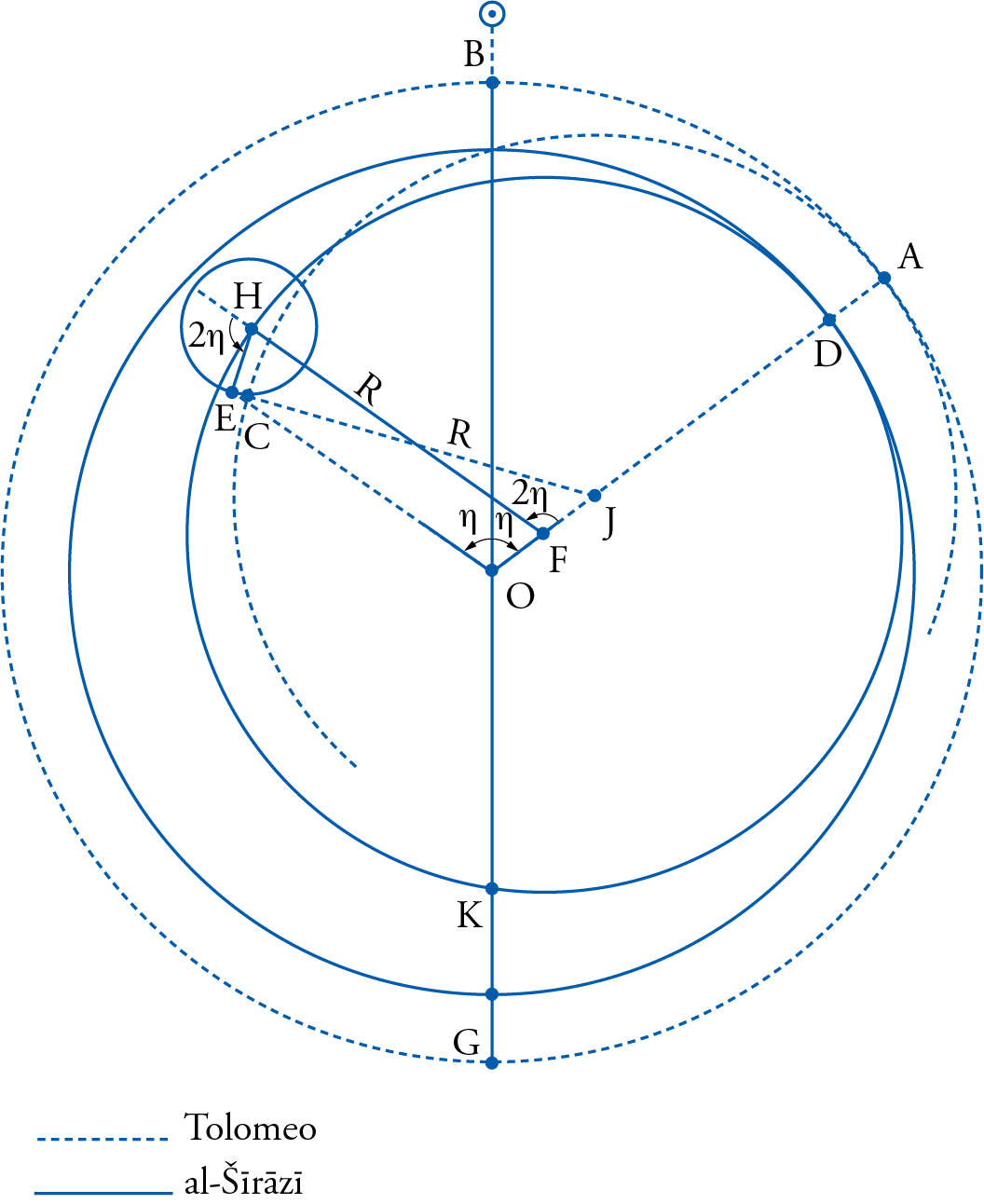

Quṭb al-Dīn al-Shīrāzī, al-Ṭūsī’s student and associate, developed yet another model of his own. In essence, it relied on al-ʿUrḍī’s lemma rather than the al-Ṭūsī couple. In fig. 20, which shows al-Shīrāzī’s model (in continuous lines) superimposed over that of Ptolemy (dotted lines), al-Shīrāzī took a new deferent with center F, placed halfway along the line connecting the center of the world to the Ptolemaic deferent center J. He then allowed this new deferent to move uniformly about its own center, rather than the center of the world as was the case with Ptolemy’s model (thus solving the first cosmological problem of the lunar equant), and in the same direction as the Ptolemaic deferent. The deferent’s motion would then bring point D, originally along the line connecting the center of the world to the Ptolemaic lunar apogee, to point H, which was now taken as the center of another epicyclet of radius equal to half the Ptolemaic eccentricity. That new epicyclet was then allowed to move in the same direction and at the same speed, thus bringing point E, the epicyclic center of al-Shīrāzī, very close to C, the Ptolemaic epicyclic center which was required by observation.

By an application of the al-ʿUrḍī lemma to lines OE and FH, one can demonstrate that those two lines will always remain parallel, thus making point E, the epicyclic center in al-Shīrāzī’s model, look as if it was moving uniformly around the center of the world, which was also required by observation. Thus, as in the case of al-ʿUrḍī’s model, upon which this one seems to be based, the problem of the equant and the variation of the epicyclic size seem to have been resolved. There remained the prosneusis problem, which was not successfully tackled by al-Shīrāzī, as was noticed by later astronomers like Ṣadr al-Sharīʿa al-Bukhārī (d. 1347), whose lunar model is taken up next.

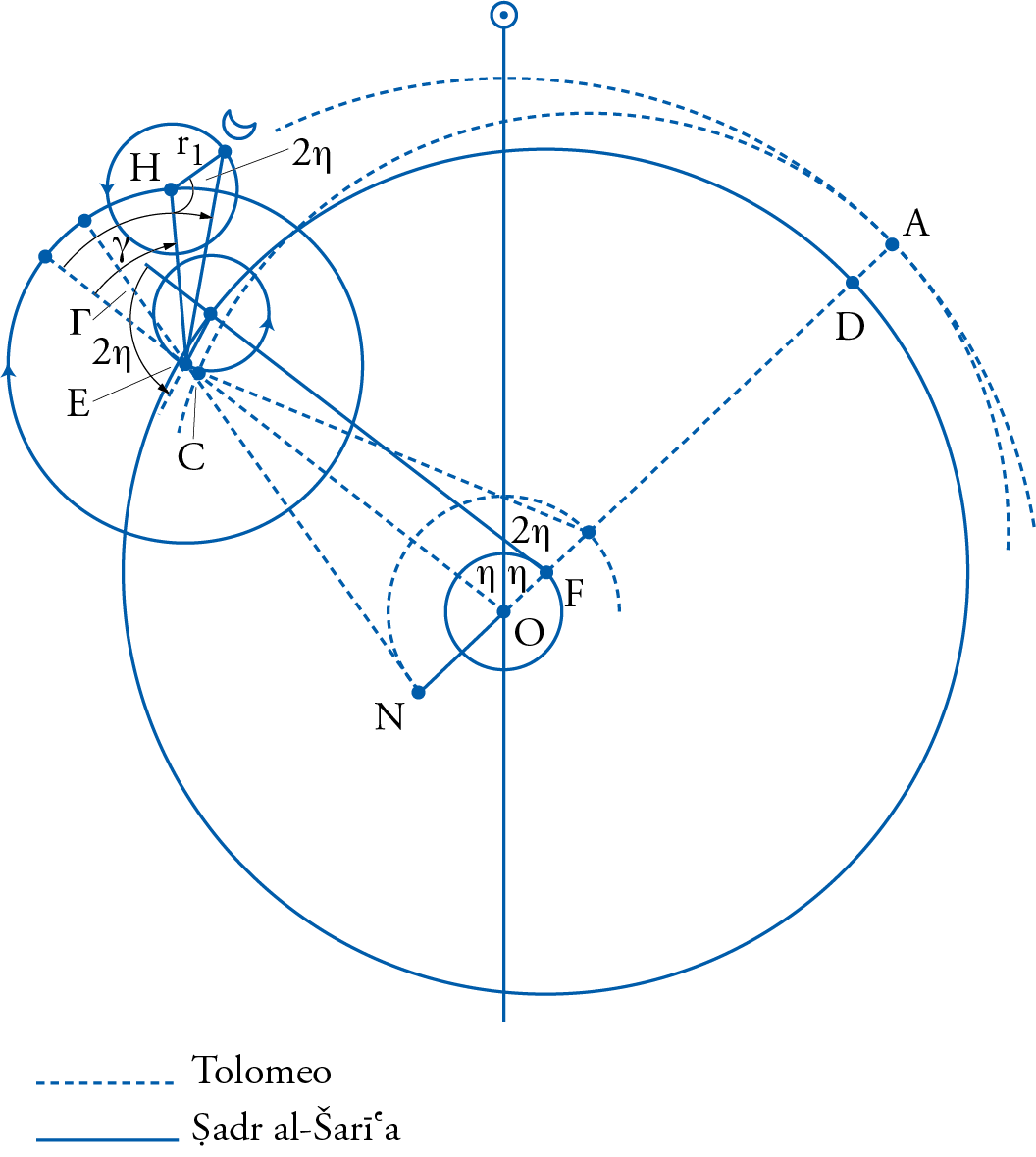

In fig. 21, showing Ṣadr al-Sharīʿa’s model (in continuous lines) superimposed over that of Ptolemy (in dotted lines), Ṣadr al-Sharīʿa essentially adopted al-Shīrāzī’s model where it solved the problems of the lunar equant and the epicyclic variation in size. He only adjusted it in an attempt to compensate for the prosneusis problem, which was left unresolved as far as Ṣadr al-Sharīʿa was concerned and for which he criticized al-Shīrāzī severely.

The method in which Ṣadr al-Sharīʿa attempted to achieve that compensation was to add to the lunar epicycle itself, here shown in continuous lines with center E, another epicyclet with center H, that was supposed to move at a speed equal to the same double elongation projected by Ptolemy, and in the same direction. But Ṣadr al-Sharīʿa also stipulated that this speed should be measured from the mean anomalistic radius of the epicycle. By giving this additional epicyclet the appropriate radius length, he could introduce a correction to the mean anomalistic motion of the lunar epicycle that was approximately equal to the one resulting from the introduction of the prosneusis point by Ptolemy. In this model, the radius of this additional epicyclet was taken to be 0;52 parts, again in the same parts that made the deferent radius equal to 60 parts.

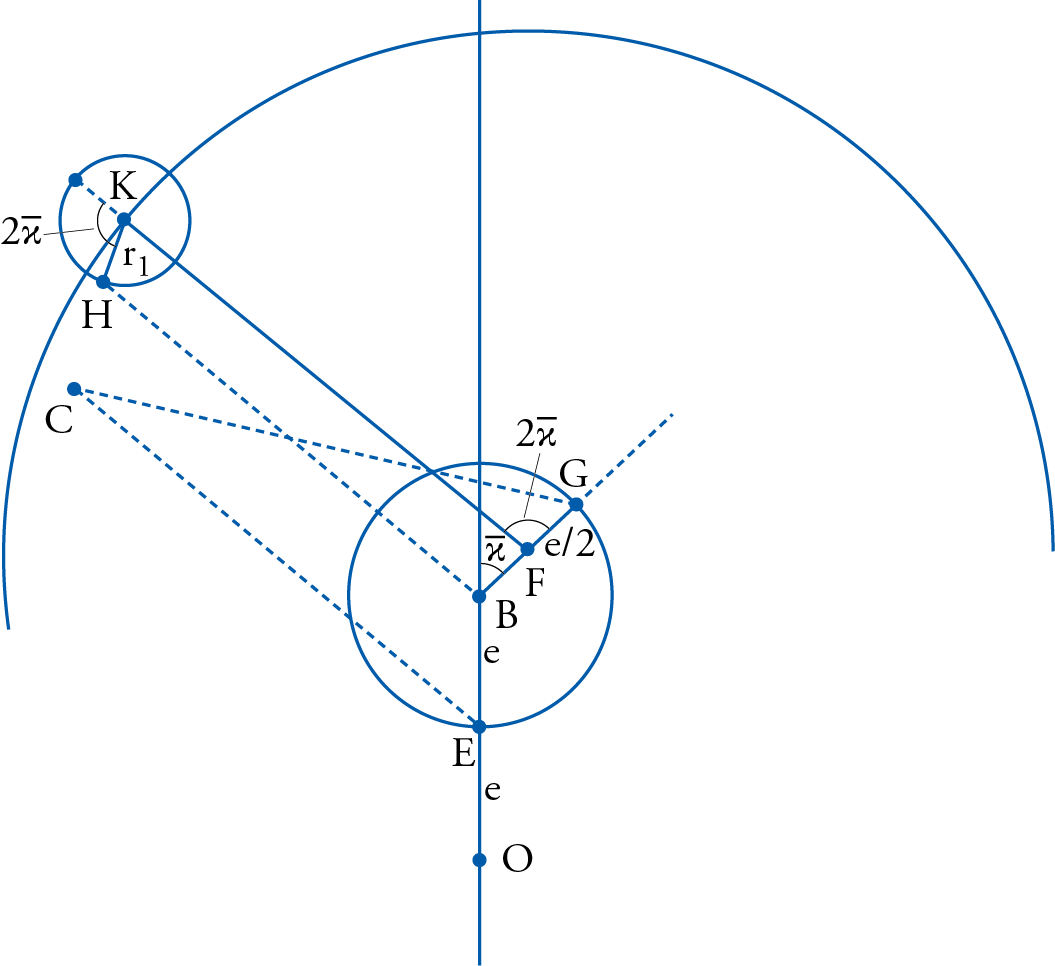

As illustrated in fig. 22, Ibn al-Shāṭir’s lunar model had the same features as his two earlier models discussed so far, namely, that it was formed of a major concentric inclined sphere, fitting within another concentric encompassing sphere, and moving uniformly around the center of the world. All other motions were accounted for by the introduction of two other epicycle-like spheres of appropriate radii and motions.

In the lunar model, Ibn al-Shāṭir gave the following dimensions to his respective spheres inside the encompassing sphere, which last one can be disregarded for the moment as it was made responsible only for the regular motion of the lunar nodes at 0;3,10,38,27° per day. The first concentric inclined sphere, here represented by radius \(r_1\), was given the usual length of 60 parts. The second sphere, referred to as the epicyclic sphere, had a radius \(r_2\) equal to 8;16,27 parts. The third sphere, called the ‘director’ (al-mudīr), had a radius \(r_3\) of 1;41,27 parts. The circular representation of those spheres, here illustrated in the diagram, takes the following dimensions when adjustments are made for the radius of the body of the Moon itself, 0;16,27 parts, which is taken to be embedded within the last sphere of the director. Then the radius of the epicyclic sphere would be taken to be 6;35 parts, and that of the director itself as 1;25 parts.

After disregarding the motion of the encompassing sphere, the motions of the other spheres could be described as follows:

- The inclined sphere moves around the center of the world at the speed of 13;13,45,39,40° per day, which is equal to the sum of the motion of the nodes and the mean longitude of the Moon.

- The epicyclic sphere moves in the direction opposite to that of the succession of signs, at the anomalistic speed of 13;3,53,46,18° per day, around its own center C, thus preserving cosmological principles.

- The director sphere moves in the opposite direction to the third at a speed equal to twice the elongation of the Moon from the mean Sun that was stipulated by Ptolemy.

These combined motions and their directions have the effect of allowing the lunar epicycle, which is carried at the tip of radius \(r_3\), to have an equation of about 5;10° at the apogee and to increase to 7;40° while at quadrature, as required by observation. Of course, the model also has the advantage of all motions taking place about axes that pass through the centers of the respective spheres.

In addition, the model also compensates for the other observational fault embedded in the Ptolemaic model, namely, the one resulting from his adoption of the crank-like mechanism in order to make the epicycle produce an angle of 7;40° while at quadrature. That crank-like mechanism also made the Moon look almost twice as large at that point, which was obviously not the case by simple observation. Ibn al-Shāṭir’s model, with its well-chosen dimensions that could account for the longitudinal motions, had the added advantage of adjusting for this additional fault as well. With the given dimensions, and while at the syzygies, the Moon’s apparent body would be at a distance from the observer between 1,5;10 and 54;50 parts, while it would appear at quadrature to be between 1,8;0 and 52;0 parts. This last distance variation at quadrature, becoming only 52 parts at the closest distance, is a tremendous improvement over Ptolemy’s expected distance at quadrature of 34;7 parts, which would be almost halfway from the distance at syzygies, and thus would make the Moon look twice as big. This last advantage, in specific, may have constituted the main reason for Copernicus to adopt in his own work, the De revolutionibus, Ibn al-Shāṭir’s model together with the dimensions given to it by Ibn al-Shāṭir.

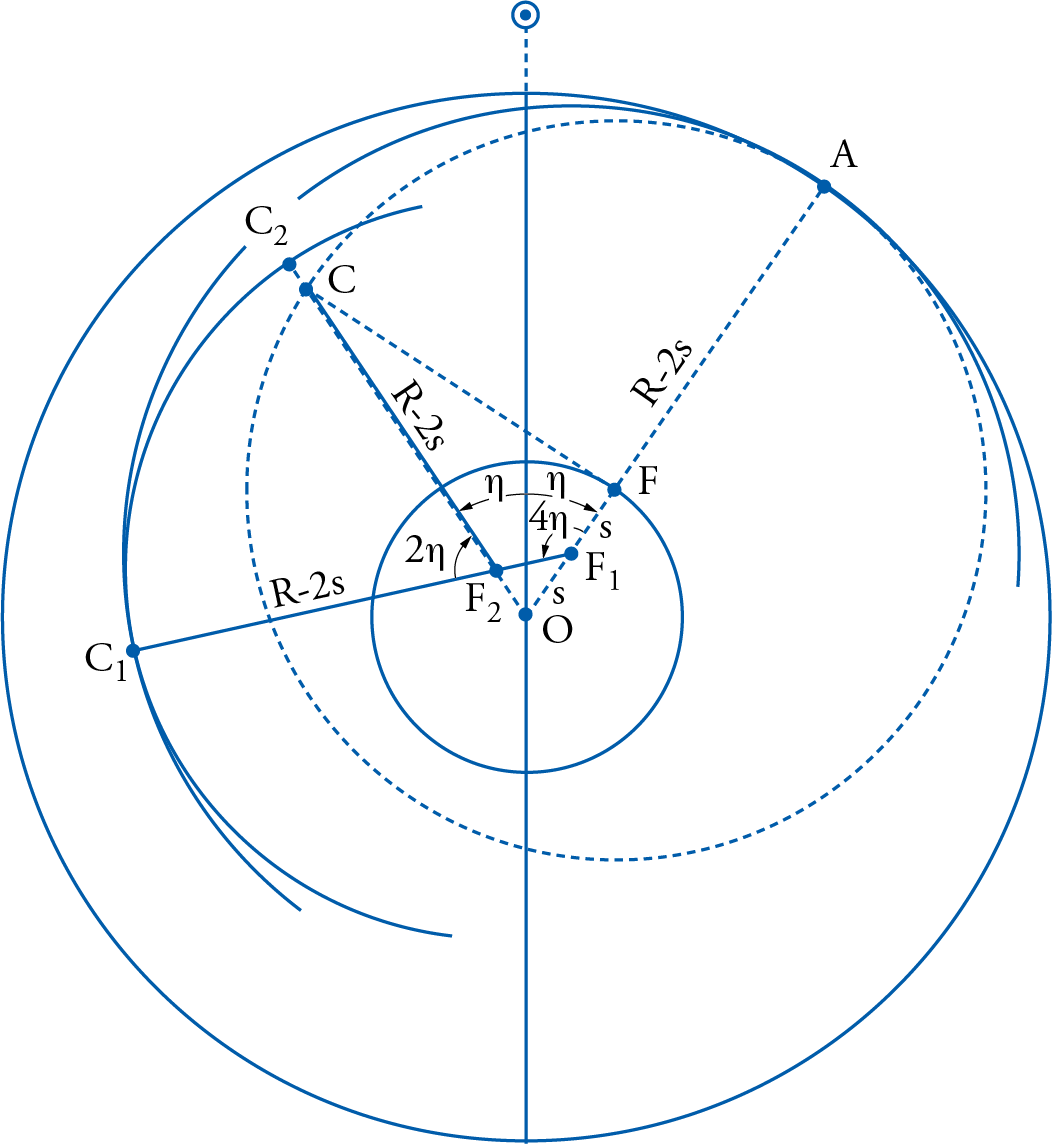

Al-Qāshī’s lunar model was in the same tradition of al-ʿUrḍī and al-Shīrāzī, for it employed the same techniques to correct the faults of the Ptolemaic model. As illustrated in fig. 23, al-Qāshī’s model (drawn with continuous lines) introduced a new deferent, just like al-Shīrāzī’s, whose center was now located at \(F_1\), halfway between the center of the world and the Ptolemaic deferent center, and whose radius was \(R–s\). He then allowed that deferent to move about its own center at a speed equal to four times the elongation stipulated by Ptolemy, a move similar to the motion stipulated by al-ʿUrḍī before.

Then within that deferent he took another eccentric, now centered at \(F_2\), with radius \(R–2s\), and allowed it to move in the opposite direction to the first deferent, i.e., in the direction contrary to the succession of the signs, but at twice the original elongation of Ptolemy. This motion had the effect of bringing the center of the lunar epicycle in line with OC, which was the required direction anticipated by the Ptolemaic model. Moreover, the epicyclic center \(C_2\) adopted by al-Qāshī would obviously coincide exactly with the epicyclic center of the Ptolemaic model, C, at the most critical points, namely, at syzygies and quadrature. It will depart from it at other positions by an amount so small that its effect on the observer at point O will not exceed an angle of 0;8,29 degrees of arc. That value was well within the 10 minutes of arc usually accepted by pre-modern authors, and by Ptolemy himself, as escaping the notice of the most skillful observers, as al-ʿUrḍī would put it.

This arrangement would obviously resolve both problems of the lunar model, namely, the equant and the prosneusis point. What remained was the observational distortion that such models would introduce when the Moon was at quadrature – distortions introduced by the Ptolemaic model, and only corrected for by Ibn al-Shāṭir as far as we can now tell.

As was stated earlier, the proximity of this planet to the Sun and its relatively short period makes it very difficult to observe, and thus the Ptolemaic model described above suffered from inaccurate representation of its motions, as well as the usual cosmological equant problem. Moreover, this planet’s motion as described by Ptolemy also stipulated that this planet’s epicycle comes close to the Earth twice during its revolution, thus producing one apogee, called the slow-moving apogee, placed on the 10th degree of Libra during the time of Ptolemy and moving together with the motion of the fixed stars, and two perigees located at 120° on either side of this apogee.

In order to account for this variation in the distance of the epicycle of this planet from the observer, a crank-like mechanism similar to that which was used in the case of the Moon was proposed here as well. But as in the case of the Moon too, this mechanism also required the uniform motion of a deferent sphere, in place, about an axis that did not pass through its center – a veritable absurdity.

All later attempts to reform this model focused on this specific absurdity, which is in essence the same as the one that was encountered in the other planetary models. The first person to try to find an alternative to the Ptolemaic model of Mercury that we know of so far was the same Muʾayyad al-Dīn al-ʿUrḍī of Damascus to whose work reference has already been made several times.

Taking inspiration from the similarities between the model for this planet and that of the Moon, al-ʿUrḍī approached the Mercury problem along the same line as that of the Moon. In essence, he took liberty with the directions of motions that he assigned to the spheres as well as to their magnitude, aiming, of course, to avoid having any one of those spheres move uniformly in place about any axis that did not pass through its center.

In fig. 25, which shows al-ʿUrḍī’s model (in continuous lines) superimposed over that of Ptolemy (dotted lines), we note that the Ptolemaic director that was centered at point B remained at that point, except that its motion was now assumed to take place in the direction of the succession of signs (opposite to that assumed by Ptolemy), and its magnitude was assumed to be three times that which was assigned by Ptolemy for the director in his own model.

As a result, the fast-moving apogee assumed by Ptolemy to be moved by the director to point T was now assumed by al-ʿUrḍī to move to point S instead. With the same dimensions of Ptolemy’s deferent for this planet, al-ʿUrḍī used another deferent whose center was now located at point K, rather than G. The motion of this new deferent was contrary to that of the director that carried it, and its magnitude was only twice as much as the mean motion of the planet that was given to Ptolemy’s director.

The combined motions of the new director and the new deferent would allow point I, which is now the center of the epicycle according to al-ʿUrḍī, to move back from al-ʿUrḍī’s apogee, S, so that line KI would become parallel to EC, which was required. As a result of this parallelism, one can easily demonstrate that, for an observer on the Earth, point I would look as if it is moving uniformly around point E, since the line connecting the center of the epicycle to the center of the deferent that carries it, when extended, forms the same angle with line OB as the one that was formed by line OC in the Ptolemaic model.

Although the difference between the two points I and C is here exaggerated in the diagram for purposes of illustration, in reality, the two lines EC and KI are so close that it would have been very difficult to depict them apart on the page of the paper if they were to be drawn to scale. Even then, and as in the case of the Moon, their difference exerts such a negligible effect on the observer at O, that it would be very difficult to detect by the most skilled observer. The advantage of this model, on the other hand, over that of Ptolemy, is that it adheres to the cosmological principles enunciated several times before, while Ptolemy’s model does not.

Independence of thought and considerable ingenuity was demonstrated by al-Shīrāzī while treating the problem of the Ptolemaic model for this planet. Knowing the circumstances of his life, one can safely assume that when al-Shīrāzī first encountered this problem, he only had the just described solution of al-ʿUrḍī at his disposal. His own teacher al-Ṭūsī, who had managed to find alternatives to all the other planetary models proposed by Ptolemy, declared his bankruptcy when it came to this planet.

All he could say in this context in his most famous and seminal work was to wish that God would grant him the insight at some future time to resolve the complexities of that model. He said that around the year 1260 and apparently died in 1274 without receiving that inspiration as far as we can now tell. But al-Ṭūsī’s efforts in resolving the problems of the other planetary models, especially his application of the al-Ṭūsī couple, were not altogether wasted. For now that very same theorem came in very handy when his student, al-Shīrāzī, took up the challenge of rectifying the work of his teacher and began to construct his own solution for this model.